Field Observations in Chiang Mai, Thailand, of Tylototriton verrucosus, the Himalayan Crocodile Newt

by Chris Michaels

Introduction

In July 2007 I spent several days in two wildlife parks in Chiang Mai province, Northern Thailand, where I was able to observe Tylototriton verrucosus in its natural habitat. The two parks in question were in Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary and Doi Inthanon National Park, both of which are at elevations of over 1000 m (3300 ft.) above sea level. I travelled with two friends; Tim Saunders, a friend from school, and Pipat Soisook, an MSc student of bat taxonomy and ecology at the Prince of Songkla University, Songkla, Thailand, whom I met through my work with the Harrison Institute in Kent, UK.

This article is not, alas, a full scientific study, but just a number of observations of amphibians in Chiang Dao and Doi Inthanon, focussing on T. verrucosus.

Taxonomic and Biogeographical Introduction

Adult T. verrucosus in the 'newt nursery' at Doi Inthanon

Tylototriton verrucosus (Anderson 1871) is widely distributed throughout South East Asia and the Indian Subcontinent, having been recorded from extreme western Yunnan province in China, Myanmar (formerly Burma), Thailand, Northern India, Bhutan, Laos, eastern Nepal and (possibly) Vietnam. Across this vast range, several 'phenotypes' of T. verrucosus are known, and the taxonomic status of this species is still unclear. Nussbaum and Brodie (1995) assigned the Tylototriton found in N. Thailand to the species T. verrucosus when they reassessed the taxonomy of the species, which had no previously designated holotype.

A neotype of T. verrucosus was designated from specimens collected in Yunnan, as close as possible to the type locality described by Anderson. At the same time, they split a new species, T. shanjing, from T. verrucosus, on the basis of significant morphological differences, and also on account of the two forms being sympatric in Yunnan, Western China.

Female T. verrucosus from Doi Inthanon. ©2007 Pipat Soisook

It is likely that, as a consequence of new research on the taxon, many of the different 'forms', possibly including those in Thailand, will be elevated to subspecific or even specific status. This is made more likely by the wide geographic distribution of the species, which is divided by several mountain ranges, and the tendency of T. verrucosus to be found in small, isolated populations, particularly in mountainous regions. Both of these distribution patterns favour speciation.

However, the T. verrucosus I saw in Chiang Mai were far more similar to the neotype specimen of T. verrucosus pictured in Nussbaum and Brodie (1995) than they are to the holotype of T. shanjing pictured in the same publication.

Chiang Dao National Park

On a hot, wet and windy day in Chiang Dao Wildlife Sanctuary, Chiang Mai Province, North Thailand, my team and I mounted on the back of a mud-encrusted pick-up truck, bounced along a steep and incomplete dirt track through the driving rain towards a remote research station. As we climbed steadily, lowland deciduous forest gave way to evergreens and bamboo and, as we ascended into the alpine mists, pine forest. The temperature dropped considerably with the height and the rain. The road itself marks a boundary between the government-owned and protected sanctuary and the forest owned as common land by the local people.

T. verrucosus habitat at Chiang Dao

Currently they choose to preserve the forest, but there are some who prefer to burn it every summer. After 3 hours, the dirt track eventually levelled out as we entered a sizeable grassy clearing and pulled up outside a group of chalet-style buildings with a neat bed of Hydrangeas in front of it. Ahead of us, the foothills and valleys, lushly carpeted in forest, rolled out. Behind us, just the other side of the solar panels that power the centre, up against the edge of the pine forest, is an area of bamboo and grass scrubland about 50 m wide and 300 m long (164 × 984 ft.).

Protected from the encroaching pines by periodic burning, this small strip of grass is home to one of the three tiny populations of Tylototriton verrucosus in Chiang Dao. This one numbered around 300 adults. The heavy rain, hailing the onset of the wet season in Chiang Mai, may have made our journey to the Station mildly uncomfortable, but with any luck should have coaxed some of the salamanders out of hiding.

Frogs

We were told by the resident researchers at the station that it would be easiest to find the newts in the daylight, rather than trying to locate them by torch-beam, and so we decided to spend the first night searching for other amphibians in a nearby stream. Armed with sticks and a machete, and of course a plastic collecting box and nets, we began to climb down the precipitous stream-bed. The water was shallow for the most part, often trickling down mossy outcrops and pouring between gnarled tree-roots, but sometimes collecting in largish pools, where the silt was thigh-deep and clouds of insects gathered.

Microhyla pulchra, Doi Inthanon ©2007 Pipat Soisook

The whole stream was choked with bamboo and banana forest, the broad leaves and crowded stems trapping the air and building the humidity; no-one had been there for a while. We were soon sweating in the muggy heat, but the loud croaks of unseen frogs kept us attentive and alert.

We reached the first good-sized pool and scanned the margins for amphibian life, spotting a number of large brown frogs, which varied from a couple of inches long to hand-size. The first animal we tried to net darted with surprising speed into the thick rusty-brown soup at the bottom of the pool, and the net yielded only large black tadpoles and mud.

Limnonectes sp., Chiang Dao ©2007 Pipat Soisook

The next attempt was successful, and amidst the silt at the bottom of the net was a large frog, the colour of the silt itself, with prominent eyes and black markings on the hind leg. Limnonectes. We put the frog into the collecting box to photograph later.

The next hour of searching yielded more Limnonectes, including both more of the first species and also a form with a creamy yellow dorsal stripe (see photograph). Unfortunately, judging from the number of tadpoles and newly metamorphosed froglets, it seemed that we had missed the main breeding season by a few weeks. A variety of peeps and croaks, as well as unidentifiable tadpoles, was the only evidence of the presence of other species.

The Newts of Chiang Dao

Adult female T. verrucosus, Chiang Dao.

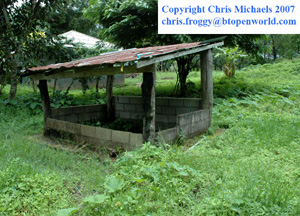

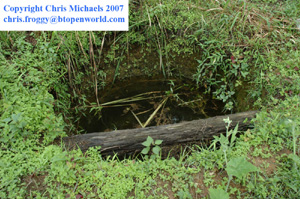

The next morning, after photographing and releasing the previous night's anurans, we walked to the aforementioned scrubland to look for Tylototriton verrucosus. Using sticks to avoid the few venomous snake species indigenous to the area, we lifted up rotting, trimmed grass where it laid in clumps around the patches of stunted vegetation. The habitat was lush and bright, but the vegetation was low-growing, in stark contrast to the shady pine and bamboo which bordered it on two sides. At one end, about 10 metres behind the station's toilet block, were two steep-sided wells dug into the red soil, one of which was covered with a wooden shelter. These ponds, with sparse aquatic vegetation and a covering of algal scum, were supposedly the salamanders' breeding sites. Five newts; two males, two females and a juvenile, were found in a relatively small area.

The adults were quite large, but more slender than the captive Tylototriton I am used to, particularly so in the males, with prominent cranial ridges and markings which varied from orange to a brown-red colour. We took the newts back to the centre to photograph and measure them, along with a sample of water from each of the breeding ponds.

T. verrucosus captured in the forest breeding pool, Chiang Dao

That same evening, Pipat, Tim and I set out for a neighbouring population armed with headlamps, buckets and nets. In the darkness we caught fleeting glimpses of several animals, mainly more Limnonectes and large skinks in our torch beams. We passed a large pond, swollen to lake size by the heavy rains, but were told that this is not the place where the newts go to breed, though I suspect closer observation might have proven this to be incorrect. At last we came to a small, stream-fed pond amongst the grasses and bamboo. At first glance we saw only more Limnonectes, a genus so common it had by now become almost a nuisance. But then something dark and sinuous rose from the gloom to the surface; unmistakably caudate. Initially tentative netting from the bank quickly became full-scale wading and over 10 adults were collected from the ooze. Nets were quickly abandoned in favour of bare hands, as the thick silt made them impractical.

Once no more newts had been caught for a little while, we headed back to the research station for more measurements.

Juvenile T.verrucosus, Chiang Dao. ©2007 Pipat Soisook

All of the newts from this pond were male; this coupled with a fairly well developed larva I collected suggested one of two things; either this was the end of the breeding season, the males staying on in the water longer than females, or that this was the beginning of the breeding season, with males arriving at the ponds before females, and some larvae overwintering in the natal pond. Kuzmin et al. (1994) described overwintering larvae, and a long breeding season (from March-May through to September in a wet year), but their study took place in Himalayan India and seems to involve T. shanjing like animals. See references for a brief discussion of the distribution implications of this. This would also explain the underweight appearance of many of the animals from both populations, particularly the males. Once we had finished measuring, Pipat and I took the animals back through the dark to the pond. Interestingly, the newts did not, as expected, disappear into the silt, but immediately tried to leave the water. Ensuring that we did not tread on our late captives, Pipat and I returned to the house with a water sample.

Unfortunately (particularly for me) our plans for netting the wells, searching the first habitat more thoroughly and photographing the second habitat the next day were cancelled by my developing acute food-poisoning during the night. The following afternoon, our pickup arrived and we made a (very uncomfortable for me!) journey back to Chiang Mai.

Well breeding pool in Chiang Dao |

Well breeding pool in Chiang Dao |

Well breeding pool in Chiang Dao |

Terrestrial habitat, Chiang Dao |

Doi Inathanon

On the 15th of July, we arrived in Doi Inthanon National Park. This park is very different compared to Chiang Dao; the vegetation was sparser and drier in the foothills, and the rock was igneous granite instead of the soft limestone of the Chiang Dao mountains.

Female T. verrucosus from Doi Inthanon ©2007 Pipat Soisook

Another great difference is that Doi Inthanon is designed for tourists; it is criss-crossed by roads which lead as close as possible to the various waterfalls and vistas, and dotted with campsites, restaurants and small villages surviving on a mixture of farming and tourism. Doi Inthanon is less wild than Chiang Dao, with evidence of people everywhere. It is something closer to British National Parks; largely preserved countryside, but largely not wild countryside, with forest clinging to the hillsides and mountains, but the valleys mostly filled with rice-paddies and villages.

We drove to the park HQ to ask permission to collect amphibians. Not only was permission granted, but we were also told about a 'newt nursery' near the campsite that we intended to use. It is a conservation centre where they breed a large number of native amphibians and fish for release into the wild.

A Day at the Newt Nursery

The captive breeding facility in Doi Inthanon is an open building, with only two walls along the long sides of the structure, inside which were banks of glass aquaria containing frogs, fish and, in the most significant numbers, Tylototriton. The setups were particularly spartan in décor, consisting of about 3 inches (7.6 cm) of water on a coarse sand substrate with a few emergent plants in small, densely populated tanks with low light levels. It appeared that the animals were fed exclusively on mealworms, and a few animals seemed particularly undernourished, one dying from a fungal infection. My immediate impression was of a well-meant effort based on inadequate knowledge of captive husbandry.

Larval tanks, 'newt nursery', Doi Inthanon National park

However, before I could take a closer look, one of the staff was keen to show us the year's breeding effort. He took us behind the building where a number of large, water-filled tubs were balanced atop a low work surface. In them are the eggs of T. verrucosus. The number of eggs, from an adult population of around 100 pairs, was surprisingly small. However, all was soon made clear. I learned through Pipat's translation that the centre was founded some 15 years ago, with an initial population of 20-30 animals, from larvae to adults, collected from the wild in the park. They now have around 100 pairs plus larvae and juveniles.

The ranger, through Pipat, told us that eggs and larvae are introduced directly into the wild habitat, as well as a number of adults from the centre. In this way, animals were generally only in captivity for as long as it takes them to mature. Once they have bred once, they are turned out into the wild and replaced by their younger progeny. This all sounded very good; many new individuals are churned out into the wild every year. However, we were told that the centre does not have the facility, resources or knowledge to record or monitor the effects of captive reintroductions on the wild population; the survivorship of re-introduced animals is anyone's guess. I do not think that it could be very high for adults as the wild habitat is so different to the captive conditions, but head-starting eggs and larvae may be quite effective (like reintroductions of Natterjack toads (Epidalea (Bufo) calamita) in Britain. Furthermore, not all of the breeding sites of the species are known, so counts at ponds may not accurate. It seems a shame to me that these breeding efforts are not fully converted into valuable conservation. In the author's opinion this centre could play a much more important role in both ecological and conservational studies, and because of the lack of facilities and knowledge, the hard work and dedication of the staff is partially wasted. This could be furthered by improved feeding regimes and husbandry techniques.

A closer look at the adult animals makes the differences between these and the Tylototriton in Chiang Dao apparent, though hard to pinpoint. The best way is to look at the photos of each and make a comparison by eye.

Furthermore, there seem to be two distinct variants within the Doi Inthanon captive population; a darker more 'verrucosus-like' form, and a lighter, stockier more 'shanjing-like' form, with broader, fleshier cranial ridges. The latter also seems less happy to be kept in aquatic setups, with most individuals perched in the emergent plants, while the darker form is largely aquatic. It is important to note that the lighter animals may be lighter in colouration because they spend more time out of the water and the skin has undergone increased sclerotisation. All this is of course a layman's observation; we weren't permitted to measure the captive animals, and photographs were poor in the dim light and dirty glass. Measurements presented herein of Doi Inthanon Tylototriton are of a single female darker form animal; no lighter form animals were found in the locality that we visited.

Interestingly, we were also told that this centre works with the Chiang Mai University and the Thai Government in trying to collect data on Tylototriton and other endemic amphibians. The details were a little unclear in translation, but it seems that a Ph.D. student is working on Tylototriton in Thailand (he receives any dead animals), and that a database has been set up by the relevant department of the Thai Government, which also collects environmental data from Chiang Dao National Park. I apologize for the vague information, but all the information I received from the centre's staff was via translation of my questions through Pipat. The crux is that the Thai Government and academic world are interested in both conservation in general, and also in understanding Tylototriton in Thailand.

Having seen all of that there was to see, we headed on to our campsite further into the hills.

The Amphibians of Doi Inthanon

Once the tents were pitched in the pine-forested campsite we waited amidst the cool humidity and cicada calls for the sun to go down, and for the amphibians to come out. Armed with head lamps and a collecting bag, Tim, Pipat and I set out into the damp night, walking slightly bent over with our eyes fixed on the ground a little in front of our feet; the characteristic "amphibian collector's walk". Almost immediately we came across a large female Tylototriton waddling purposefully over the damp grass near a drainage ditch.

Adult Ichthyophis kohtaoensis, Doi Inthanon

We quickly picked her up, but before she disappeared into the bag, I noticed she was much darker and stockier than the Chiang Dao newts, with fleshier, broader cranial ridges. A few metres from the newt, on the same patch of damp lawn, was one of the amphibians I was most keen to find on the trip; Ichthyophis kohtaoensis, the Koh Tao Banana Caecilian. Coiling round the grass-stems in response to the torchlight, it looked like a wet, elongated humbug crossed with a worm or a snake, with tiny black eyes thrown into the mix. Having photographed it, we moved on, leaving it to forage for worms.

First Camp-site, Doi Inthanon

The night's collecting yielded a number of frogs, including Microhyla pulchra?, Rana schmackeri (a Doi Inthanon endemic), and dozens of House Geckos (Hemidaktylus sp.). Unfortunately no more newts were found, despite thorough searching. Apparently, when the grass verges are trimmed back, many newts are found in the area by workmen, but the grass was cut only a week or two before our visit, so there weren't many newts around; they had disappeared into the bamboo forest with its deep blanket of fallen leaves and branches. The forest around the campsite was denser than that of Chiang Dao. We took the newt we collected earlier back to camp to measure and photograph her, and then returned her to the stretch of grass where she was found. The constant heavy drizzle of the night proved Tim's and my own doubts about the waterproofing of our tent to be well-founded.

Up the Creek without a Paddle (or a Boat)

Ansonia inthanon, Doi Inthanon National park ©2007 Pipat Soisook

Stream in Doi Inthanon National park

The water was cold and waist-deep at some points, with a loose boulder and pebble bottom. The banks were steep, sometimes covered in dense vegetation and ants that bit if one tried to climb.Attempts to stay relatively dry were quickly abandoned as we waded upstream across boulders and fallen trees. Suddenly, our light picks out a pale, mottled frog with large toe pads and wide eyes (Amolops marmoratus, the Northern Cascade frog) on a mossy boulder in the middle of the torrent. We quickly captured it before it could escape into the water. As we continued along the river we caught a few more Amolops as neared an upstream waterfall. Then, on a shingle beach we saw something jump. Moving closer, we found a very rare little toad; Ansonia inthanon, the Inthanon Stream toad, another endemic species to the region. Having collected the toad, we climbed the steep bank and walked back to the tents, where we photographed the anurans. We then released them at the water amongst the boulders.

Implications for Captive Care

Observing T. verrucosus in the wild was informative with regard to modifications that could be made to the captive care of these animals. Firstly, all of the animals in the wild were significantly slimmer than those in captivity, as are the animals photographed in the referred papers (though some are preserved, which might affect the physical appearance). Anyone keeping this species will know how greedy it can be, and having seen the natural size of these newts it is this enthusiast's opinion that obesity is a serious problem for captive specimens, particularly of the "small, dark, aquatic form".

The number of anuran tadpoles in the breeding ponds and observations by Kuzmin et al. (1994), suggest that these are a major food source during the breeding season, so perhaps this should be mirrored by an increase in protein in the diet during breeding periods.

These newts have a long breeding season in the wild, as suggested by Kuzmin et al. and various personal comments by park employees in Chiang Dao and Doi Inthanon. This may favour a largely aquatic husbandry system for maintenance of the species in captivity. However, a short, cooler and drier terrestrial phase, particularly for juveniles, may be closer to the natural conditions for these animals, despite slowing growth rates.

All of the T. verrucosus ponds we visited were both sparse in aquatic vegetation, with a thick mud bottom, and very low in nitrates and nitrites. This suggests that although this is a largely pond-dwelling species (with a maximum of slight water flow), it does require clean water in order to thrive. I believe that the low levels of nitrogenous compounds in the water occur because of filtration of rain run-off by the bamboo and grassland surrounding the ponds.

A more naturalistic captive setup for T. verrucosus from this region of their range may involve fewer aquatic plants, and more emergents such as bamboos and grasses/sedges.

Where adults were found on land, beneath piles of trimmed grass, they were in a significantly cooler and damper environment than the surroundings. For terrestrial T. verrucosus, an opportunity to burrow beneath something like cut grass may be useful.

In Doi Inthanon, where the newt was collected at night, the outside temperatures were considerably lower than the day temperatures, due to a fine, cold, misty drizzle, indicating that it may be important for animals to have cooler retreats whilst terrestrial.

The ponds were warm, but not excessively so; probably in the range of 22-24°C (71-75°F); this was the consensus of those of us who waded in the ponds - airport staff wouldn't allow my thermometer onto the plane.

Conclusion

I would have liked to have spent significantly more time studying Thai Tylototriton, but I did find the trip to be both interesting and informative in a scientific respect, not to mention fun. I would very much like to return to collect more comprehensive data. It is apparent to this author that there is much taxonomic, ecological and conservational work to be done on the Tylototriton in Chiang Mai. This is especially true in the National Parks where it lives so close to man, yet its habits and needs are barely understood. The Thai Government is clearly interested in active conservation, which is, obviously, good for all native species, and will hopefully mean that the forests of Chiang Dao and Doi Inthanon, amongst many others across the country, will not fall to loggers and developers. Pipat and his colleagues at the Prince of Songkla University and the Chiang Mai University are evidence that a new generation of keen and skilled ecologists, taxonomists and conservationists are being supported and trained. International schemes such as the Darwin Initiative project underway between Prince of Songkla University and the Harrison Institute (a centre for systematic and biodiversity research in the United Kingdom), are linking scientific researchers and organizations, and thus knowledge and resource bases. The big game has all but disappeared from Thailand; elephants and tigers are no longer heard or seen in the jungles of Chiang Dao and Doi Inthanon. However the future prospects for the indigenous amphibians, and other small animals, seem hopeful, if not sunny.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Pipat Soisook for his tremendous help in organising our field trips. Without Pipat very little would have been done, said or understood. Thanks to Tim Saunders for general help in catching newts and frogs, and of course in planning and financing our trip. Many thanks also to the Harrison Institute, without whose work and support I would not have met Pipat, or travelled to Thailand. Last, but of course not least, thanks to Ariya Dejtaradon (another student at PSU) who helped to organise the Chiang Mai part of our trip, though she could not be present there, and also our stay in Bangkok.

References

Anderson, J. 1871 DESCRIPTION OF A NEW GENUS OF NEWTS IN WESTERN YUNAN

[sic].

Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1871:423-425

Kuzmin et al, 1994 ECOLOGY OF THE HIMALAYAN NEWT (TYLOTOTRITON VERRUCOSUS)

IN DARJEELING HIMALAYAS, INDIA

Russian Journal of Herpetology Vol. 1, No. 1, 1994, pp. 69 - 76.

Nussbaum, Brodie and Datong, 1995. A TAXONOMIC REVIEW OF TYLOTOTRITON

VERRUCOSUS, ANDERSON (AMPHIBIA: CAUDATA: SALAMANDRIDAE). Herpetologica

51(3), 1995, 257-268

Article © 2009 Chris Michaels. Posted on Caudata Culture with permission of the author, February 2011.