| Ambystoma mexicanum | |||||||||||

| Axolotl | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| A leucistic axolotl. |

Description

The Axolotl is the largest member of the family

Ambystomatidae, with specimens over 43 cm (17 inches)

total length known, though typical adult length is

somewhere between 20 and 28 cm (8 - 11 inches). Unlike

most of the group, this species exists totally in the

perrenibranchiate state, retaining some larval features

into adulthood (gills, larval skin morphology, caudal

fins, etc). It becomes sexually mature in this state, and

it develops small rudimentary lungs with which it can

augment gaseous exchange if necessary, hence the term

"cryptic metamorphosis". Suspected to be an

offshoot from the Tiger Salamander complex (Ambystoma

tigrinum, A. mavortium, etc), metamorphosed

specimens bear close resemblance in pattern and

colouration to the sympatric race of Tiger Salamander, A. valasci, though exact scientific

nomenclature has yet to be resolved. Most scientific

authorities recognise that it is a true obligatory

neotene (Gould 1977), that can only be induced to

metamorphose by hormone treatment. Accounts of

spontaneous metamorphosis are generally attributed to the

influence of hybridisation with the tiger salamander, or

in some cases, to water chemistry: unusually high levels

of iodine can affect the levels of growth

hormones.

Axolotls are often prized for their variety of color mutants. Here, an albino, a golden albino, and a black melanoid.

Several other members of the Ambystomatidae occur in wholly perrenibranchiate populations in Central America, including A. andersoni, A. taylori and the CITES-listed A. dumerilii, the last species being noted for its hyperfilamentous gills. Although these are all sometimes referred to as axolotls, the name "axolotl" is best confined to the species Ambystoma mexicanum.

Captive axolotls come in many colour varieties, including the traditional wild type (brown, grey or almost black, with dark spots), albino (golden with pink eyes), leucistic (white with black eyes), melanoid (absence of iridescent pigment and very little yellow), axanthic (lacking iridescent and yellow pigment), and any combination of these, such as white albino (white with pink eyes), or melanoid albino (white with almost invisible yellow spots and no shiny pigment).

Natural Range and Habitat

The Axolotl was originally native to Xochimilco and

Chalco, two freshwater lakes south of Mexico City. Sadly,

Chalco is now gone, and Xochimilco survives only as a

network of canals and lagoons. These bodies of water are

muddy bottomed and rich in plant and animal life.

An appopriate setup for a group of axolotls. Fine sand is used to prevent problems associated with gravel ingestion. A large volume of water buffers the system against water quality problems. A large number of hiding places and visual barriers help to prevent problems with aggression. |

Housing

Never leaving the water, these salamanders require

completely aquatic conditions. A 60 x 30 x 37 cm (24 x 12

x 15 inches) aquarium is

adequate for two adults. Water depth is not important,

but 15 cm (6 inches) or more is recommended. Not being

used to small gravel in their natural habitat, substrate

should consist of either sand or rocks that are much larger than the animal's head.

Axolotls feed by evacuating their mouths of water, then

suddenly opening them very wide, thus causing anything in

the immediate vicinity to enter, be it food or substrate.

Ingestion of substrate occurs even if the axolotl is hand-fed. An aquarium bare

of substrate, while perhaps less attractive, is safest

and generally easier to clean. In the wild, the water

temperature in Xochimilco rarely rises above 20°C (68°F),

though it may fall to 6 or 7°C (43°F)

in the winter, and perhaps lower. In captivity, any

temperature between 14 and 22°C (57 to 72°F) is reasonable for adults. Any temperature over 25°C (77°F) is unsuitable for anything more than a few days.

High temperatures stress axolotls, and anorexia, fungal

and bacterial infections often result. Filtration, if

required, can be accomplished in any of the usual ways,

but it is known that axolotls are stressed by flowing

water, so make sure that the water flow from a power

filter, for example, is reduced or diffused in such a way

as to prevent large volumes of water flowing about the

tank at speed. Plants are not essential, unless breeding

is planned. In any case, either choose robust plant

species or those easily replaced, because axolotls tend

to dredge up and damage delicate plants in their tank.

Hiding places, though not essential, are a good idea -

axolotls seem to like to have the option to hide at times.

Lighting is not required either, unless ease of viewing

is required. Remember to ensure water quality is

maintained by making regular water changes - 20% or so

every two weeks is usually adequate unless large numbers

are being kept in a small tank or overfeeding is taking

place. Remember to treat tap water with a water

conditioner prior to use as it may contain harmful

substances (chlorine, chloramine, metals). For more information, see water quality.

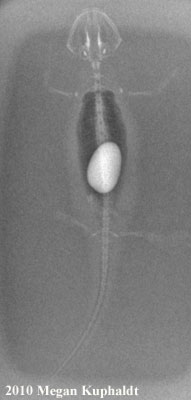

This axolotl swallowed blue gravel, which can be seen in its abdomen. In some cases, gravel passes through the digestive tract. In other cases, it causes digestive impaction, sometimes leading to death. Gravel is thus unsuitable for use with axolotls. |  This axolotl swallowed a large stone from its enclosure. |

Feeding

Axolotls are voracious feeders. They will eat earthworms,

tubifex worms (live, frozen, or freeze-dried - sometimes

incorrectly labelled as "bloodworms"),

bloodworms (the larvae of chironomid midges), blackworms

(an aquatic relative of earthworms), crustaceans like

shrimp, pieces of fish (avoid salted fish and marine fish),

strips of beef heart or other lean red meat, small

invertebrates like insects, tadpoles and feeder fish. The

last two should probably be avoided because they often

harbour parasites, and these can be passed on to the

axolotls. Most axolotls will also eat the sinking pellets

sold commercially to feed trout and salmon. These are an

excellent food. Products such as Tetra's Reptomin will

also be eaten, but because they float, they're generally

not ideal. For nutritional comparisons, see Foods for Caudates and Nutritional Values of Amphibian Foods.

Large adult axolotls will consume several whole "night crawler" earthworms with no difficulty. The warmer the axolotls are kept, the more regularly they should be fed. As much food as they will eat in 15 minutes is a good guide. If kept at 22°C (72°F) they should only require feeding every two to three days. Don't leave food to spoil the water after feeding.

Metamorphosed leucistic axolotl. |

Metamorphosed wild type axolotl. |

Breeding

Axolotls can reach sexual maturity anywhere between 6

months and in excess of a year, usually at about 20 cm (8

inches). Sexually mature males have a much more swollen

cloaca than sexually mature females. It's generally a not

a good idea to breed female axolotls until they reach at

least 18 months of age. This gives them time to reach

their full size and condition. Most sources state that

the breeding season for axolotls is from December to

June, although most success is reported in December and

January, though breeding can take place at any time of

the year. If the water temperature and light levels are

allowed to vary throughout the year, spawning will

usually take place in late winter. If kept at roughly the

same temperature throughout the year, spawning can take

place at any time. Some people recommend a sudden

decrease in water temperature to stimulate breeding, but

this generally only stimulates the male, but if the water

temperature is allowed to vary with the seasons, though

not allowed to get too warm in summer, mating usually

takes place once or twice a year in winter. Female

axolotls shouldn't be allowed to breed more than once

every two months for health reasons.

The breeding tank should be furnished with plants (plastic plants are good because they don't rot) for the female axolotl to affix her eggs. Flat, rough pieces of stone should be placed on the bottom of the tank onto which the male can deposit his spermatophores.

Axolotl spermatophore (clear stalk with white cap). |

Female axolotl laying eggs. |

After the courtship dance and uptake of the sperm capsule by the female, it's a good idea to remove the male. Spawning takes place between a few hours and two days later. Eggs are laid individually, usually on plants. There may be between one hundred and over a thousand eggs laid in one spawning, depending on the size of the female. After the female has finished laying, it's best to remove her too. Eggs hatch after 14 days at 24°C (75°F), and after a few hours, the larvae will begin to eat anything small enough to fit in their mouths. Young daphnia, micro worm, and newly-hatched brine shrimp (minus the cyst shells) are ideal first foods. Once the larvae are 3 cm (just over 1 inch) in length, they can take larger foods, such as frozen bloodworm, chopped earthworms, chopped tubifex and white worms. Most bloodlines of axolotl are quite cannibalistic, so don't keep many in one tank. At 24°C (75°F), they should be fed twice a day as much as they will eat in 20-30 minutes, until they measure 10 cm (4 inches). Less frequent feedings will result in lots of lost limbs, gills and deaths. At lower temperatures they can be fed less frequently. Once past 15 cm (6 inches), they become more docile. Well fed and kept at 24°C (75°F) it is possible for them to reach 25 cm (10 inches) and sexual maturity in less than 6 months.

Eggs approximately 11 days after laying. Click for larger image. |

Larva approximately 2 weeks after hatching. Click for larger image. |

Larva approximately 6 weeks after hatching. Click for larger image. |

Larva approximately 8 weeks after hatching. Click for larger image. |

Other Resources

References

Armstrong, John B. and Malacinski, George M. (1989). Developmental

Biology of the Axolotl. Oxford University Press.

Balsai, Michael J. and Lewbart, Gregory A. (1994). Axolotls. Reptile & Amphibian magazine. (March/April):40-51.

Duellman, William E. and Trueb, Linda (1994). Biology of Amphibians. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ezendam, Thomas (1994). De axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) [the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)]. Het Terrarium. 12 (5):95-96.

Fenske, Reiner; Köhler, Ulrich; Kretzschmar, Klaus (1995). Haltung und aufzucht des axolotls Ambystoma mexicanum (Shaw, 1798) [Husbandry and breeding of the axolotl Ambystoma mexicanum (Shaw, 1798)]. Sauria. 17 (1):21-25.

Gould, S. J. (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Indiviglio, Frank (1997). Newts and Salamanders: a Complete Pet Owner's Manual. Barron's Educational Series.

Moore, Gary (1994). Keeping axolotls in captivity. Reptilian. 2 (2):33-38.

Schreckenberg, G. M. and Jacobson, A. G. (1975). Normal stages of development of the axolotl, Ambystoma mexicanum. Developmental Biology. 42 391-400.

Scott, Peter W. (1981). Axolotls: Care and Breeding in Captivity. TFH Publications.

Smith, Hobart M. and Smith Rozella B. (1971). Synopsis of the Herpetofauna of Mexico. University Press of Colorado.

|

|

©2001 John Clare. Posted January 2001.