| Amphiuma pholeter | |||||||||||

| One-toed Amphiuma | |||||||||||

| Amphiuma means | |||||||||||

| Two-toed Amphiuma | |||||||||||

| Amphiuma tridactylum | |||||||||||

| Three-toed Amphiuma | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

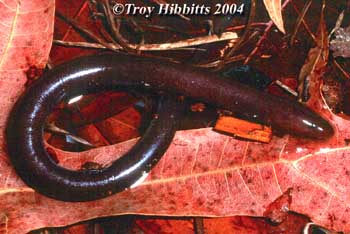

| Amphiuma tridactylum |

Description

The three species of the Amphiumidae appear very similar to each other, with the primary difference being in the number of digits on each limb. Amphiuma pholeter has one digit on each foot, Amphiuma means has two, and Amphiuma tridactylum has three. In other respects, the species are similar, although there is a significant size difference between A. pholeter and the other two species at maturity. Another difference between A. pholeter and the other two species is that A. pholeter lacks costal grooves, while A. means and A. tridactylum have 57-60 costal grooves. All three species have long bodies, flat pointed heads, and vestigial limbs.

There is a wide variety of colloquial names for these salamanders, including "congo eel", "conger eel", "ditch eel", "lamp-eater", and "congo snake". However, the accepted common names are based on the number of toes on their feet: one-toed amphiuma, two-toed amphiuma, and three-toed amphiuma.

Amphiuma pholeter, the one-toed amphiuma, has limbs and a head that are proportionately shorter than A. means or A. tridactylum. In addition, A. pholeter has a single gill opening on each side of the head and very small eyes. The dorsal and ventral areas of the salamander are of almost the same shade and are usually a darkish gray or grayish-brown. Adults of this species reach a maximum of 33 cm (12.9 inches) in total length, making this the smallest of the three species. There are no recorded conspicuous external sexual characteristics.

Amphiuma pholeterAmphiuma means, the two-toed amphiuma, is the largest of the three species, reaching a maximum size of 116 cm (45.6 inches) in total length. The laterally compressed tail can compose up to 25% of the total body length. The ventral surface is lighter in color than the dorsal surface, but does not sharply contrast with the dorsal surface. The dorsal color of this salamander ranges from black to dark brown to gray, although there are records of the occasional albino. As with A. pholeter, the eyes are small, and there is a gill slit on each side of the head. There are no recorded conspicuous external sexual differences.

Amphiuma means

Amphiuma tridactylum, the three-toed amphiuma, is the second largest of the three species reaching a maximum size of 106 cm (41.7 inches) in total length. The laterally compressed tail can compose up to 25% of the total body length. As with the other two species, the eyes are small, and there is a gill slit on each side of the head. This species has the most contrast between the dorsal and ventral coloration, resulting in a sharply bicolored salamander. The dorsal coloration consists of black, slate gray, or a brownish color, while the ventral surface is light gray with a dark patch on the throat. Occasional albinos have been recorded from Mississippi and Missouri. A. tridactylum is sexually dimorphic, with females having dark cloacal walls while the males have whitish cloacal walls with oval papillose patches located on the lateral walls. (The inner cloacal walls can be observed by gently spreading open the walls, or waiting for a time when the cloaca is flexed and the inner walls can be seen.) During the reproductive season, sexually mature males will also develop a swollen cloaca.

Amphiuma tridactylum

Natural Range and Habitat

All three species are restricted in distribution to the southeastern United States. The one-toed amphiuma has the most restricted range, occurring only in the northwestern portion of the Florida panhandle and in the southeastern portion of the gulf coast of Alabama. The two-toed amphiuma occurs throughout mainland Florida, west to Louisiana, and eastward along the coastal states to as far north as Virginia. The three-toed amphiuma occurs in the gulf-coast states from western Alabama, westward through Mississippi and Louisiana to eastern Texas, and north (following the Mississippi River) through much of Missouri and into eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, and extreme western Kentucky.

Amphiuma species are aquatic, although they periodically can be found on land at night during rainstorms or when the females are brooding eggs. The normal habitat for all three species is either permanent or semi-permanent bodies of water such as canals, ponds, ditches, sloughs, rivers, or streams. All three species live in burrows in the mud at the bottom of the waterway, such as those made by crayfish In addition, all three species are able to make their own burrows. If the body of water in which the amphiumas reside dries up, they will burrow into the mud where, depending on the species and size, they can usually survive until the next rain.

Amphiuma means |

Amphiuma pholeter |

Housing

A. pholeter, the smallest of the three species, can be maintained in small groups of up to five individuals in a 76-liter (20-gallon long) aquarium. This species mainly dwells where soft mud gives way to firmer substrate at the bottom of the body of the water. This can be simulated by adding several inches of organic topsoil (make sure it does not contain manure or other soil amendments) and several handfuls of dried leaves to the aquarium when it is filled with water. This will provide the amphiumas with a habitat similar to that found in the wild. The only difficulty with this set up is that this prevents use of any power filter, as the filter will stir the up the mud and become clogged. The addition of floating plants such as duckweed, bladderwort, or water sprite will also help to mimic the natural habitat of this species. The major drawback to this sort of enclosure is that the animals will rarely if ever be visible. If viewing the salamander is important, then the soil can be omitted, but the addition of several handfuls of leaves to provide shelter on the bottom and a thick layer of floating plants should be provided. The best sort of filter for this sort of enclosure is a sponge filter, and weekly water changes of 10-15% should also occur.

The housing requirements for A. tridactylum and A. means are the same and consequently will be covered together. Cage size requirements are not as large as one might expect for a salamander of this size if housing the animal singly. For a strictly temporary set-up, they can be kept in buckets filled about 1/4th of the way with water, with a secure lid over the top. Plastic storage bins can be used for long or short-term maintenance, as long as the bin is sized appropriately to the size of the salamander. Longer, wider enclosures should be chosen over higher, narrower enclosures. The bin should have 1-cm (0.5-inch) holes drilled in the lid for ventilation, or the center region of the lid can be cut out and fiberglass screen siliconed in place to prevent escapes. The use of the screen will allow visual checks of the animals without having to open the lid. The lid should be securely attached to the bin at all times to prevent the salamander from pushing the lid up and escaping. With larger animals, an enclosure at least 0.5 meters (1.5 feet) high is a good choice, as it prevents the salamander from routinely rubbing its snout on the lid while attempting to escape. The minimum depth of the water for these two species should be 10-15 cm (4-6 inches). The lids of plastic storage bins may be better than screen lids on aquaria. A large, active amphiuma may rub its snout on the screen if the screen lid covers the entire top of the enclosure.

If the goal is to attempt to reproduce the salamander in the long run, then an enclosure at least as wide and as long as the largest amphiuma to be housed in the tank is a good starting point. This tank should have multiple shelters on the bottom of the aquarium to allow each animal to choose its own hiding place. An easy method is to use PVC pipe that is as close as possible to the diameter of the amphiuma and as long as the largest amphiuma to be housed. There should be at least two pipes for each animal to allow each one to choose its own preferred hiding spot. Over this there should be maintained a thick layer of floating plants, and the aquarium should be well filtered preferably with a canister or other large filter. The returning current flow can be regulated by valves and a spray bar placed underwater.

Although filtration is not necessary, it reduces the need for frequent water changes and helps to maintain a stable water quality as bacteria that metabolize the waste products become established in the filter bed. Water changes should occur at a minimum of once a week in filtered enclosures, but may be necessary as often as once a day in unfiltered enclosures to remove shed skin and uneaten prey and prevent fouling of the enclosure. All of the water used for water changes should be dechlorinated and aged. Distilled, rainwater, and/or reverse osmosis water should only be used to replace evaporated water, as these sources of water lack sufficient ions and may cause calcium loss to the salamander. If the local tap water contains high amounts of minerals, then spring water can be used as an alternative. All filter equipment in the enclosure needs to be firmly secured to prevent the amphiuma from dislodging the intake or the outtake of the filter. The intake of the filter should be firmly covered to prevent entrapment and resulting injury or death.

These animals do not need heated enclosures, as they are all found in areas where the temperature can get well below 4.4°C (40°F). As an example, A. tridactylum is native to regions where the waterways can freeze over for weeks at a time. The temperature of the enclosures should not be allowed to rise above 26.7°C (80°F), as thermal stress may occur. Heating the tank may in fact be counterproductive, as this may prevent the salamanders from receiving thermal cues for reproduction.

Amphiuma tridactylum |

Amphiuma tridactylum |

Feeding

In the wild, amphiumas eat nearly anything that they can catch, including various invertebrates such as worms, crustaceans, and snails. The two larger species also eat fish, frogs, salamanders, and even small snakes. A. pholeter in captivity does well on a diet of blackworms, but will also take small crickets, wax worms, small earthworms, and other small invertebrates. In captivity the two larger species will often accept some pelleted food, as well as small fish, frogs, tadpoles, crayfish, raw or cooked shrimp, and other prey items. Amphiumas will eat smaller salamanders, including conspecifics, so animals housed together should be of similar size. Long forceps or hemostat can be used to individually hand-feed animals to prevent injuries to each other from feeding responses. These injuries can occasionally be fatal. An alternative method for feeding is to maintain a small population of freshwater shrimp or crayfish in the aquarium at all times, both as a food source and as scavengers for uneaten food. This will allow the salamanders to feed as necessary to supplement hand-feeding.

Care must be taken to avoid being bitten. The bite of an amphiuma is said to be painful, though rarely of medical significance. There are reports of amphiuma bites requiring stitches. As a maintance diet, the salamanders should be fed to satiation once a week, but if the animals are being conditioned to attempt breeding, then multiple feedings each week may be necessary.

Amphiuma pholeter |

Amphiuma pholeter |

Breeding

Internal fertilization occurs through the direct transfer of the spermatophore. The courtship and reproductive process in A. pholeter has not been recorded yet, and the understanding of courtship in A. means has large gaps in our knowledge. Reproduction of A. tridactylum is the best documented of the three species. In this species, males court a female by swimming around her in an elaborate spiral, sometimes in large groups. The females lay clutches of roughly 100 eggs in a burrow or under an object near the edge of water. The eggs are presumably laid under the water, but as the water level recedes, the eggs are exposed. Females are often found incubating or guarding the eggs. Oviposition is believed to mainly occur during the warm months, but hatching is most common in October and November, though it has been documented to occur as late as the following May. Incubation time is approximately 4-5 months (see Petranka 1998 for more information).

If captive breeding is to be attempted, then the animals should be exposed to a temperature drop and, later, an increase. Concurrently, there should be a decrease and then increase in the photoperiod.

Conservation

There are no large scale breeding programs for these species, thus those that are available from supply companies are invariably wild caught. Though this trade does not appear to have an adverse impact on wild populations as a whole, care should be taken to not over-harvest these species. Breeding programs for these species should be developed to reduce or eliminate the potential risk to wild populations. As with most other animals, habitat destruction and possibly the introduction of exotic species are putting these interesting salamanders at risk throughout their range.

Amphiuma means

References

Conant, R. and J. T. Collins. 1998. A field guide to Reptiles and Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston.

Means, D. Bruce. 1996. Amphiuma pholeter. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 622: 1-2.

Petranka, James W. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London. 587 pp.

Salthe, Stanley N. 1973. Amphiumidae, Amphiuma. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 147: 1-4.

Salthe, Stanley N. 1973. Amphiuma means. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 148: 1-2.

Salthe, Stanley N. 1973. Amphiuma tridactylum. Catalog of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 149: 1-3.

Related Resources

AmphibiaWeb account for Amphiuma means.

© 2004 Ed Kowalski and Greg Watkins-Colwell. Written May 2004.