| Cynops ensicauda | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

| Cynops ensicauda popei |

Conservation Status

Cynops ensicauda is included in Japan's Red List of Threatened Amphibians. The Red List, published by Japan's Environment Ministry, states the risk of extinction based on biological data. Cynops ensicauda has, since 1999, been included in the category of Near Threatened (NT). This category is defined as "species facing a difficulty in maintaining a viable population". The species was internationally listed as "Endangered" in the IUCN's "Red List of Threatened Species" in April of 2004 (www.iucn.org), based on the results of a "Global Amphibian Asessment" (www.globalamphibians.org), documenting the limited range, major threats, and declining adult population of this species. At present, the species still occurs in the Japanese pet trade. Although exported regularly from Japan in the past, this species is seldom seen in international trade today. C. ensicauda popei is more commonly found in captivity than the nominate subspecies. Both subspecies are bred in captivity.

Description

Cynops ensicauda consists of two subspecies, C. ensicauda ensicauda (the so-called nominate form) and C. ensicauda popei. The two subspecies inhabit different islands in the Japanese Ryukyu Archipelago. Cynops ensicauda is also the largest still-existing species within the genus Cynops. (Cynops wolterstorffi, another large species, lived in Lake Kunming in China, but is believed to be extinct). Adults normally reach lengths of 11 to 14 cm. Maximum lengths that have been documented are 12.7 cm (5.0 inches) for the male and 18 cm (7.1 inches) for the female. Ages exceeding 20 years have been reported for this species in captivity, with the females often still laying eggs at this age.

This species is closely related to the Japanese fire-bellied newt (Cynops pyrrhogaster), which is the second species of this genus in Japan. The two species are similar in overall appearance, but C. ensicauda has a broader head, the parotoid glands are less prominent, and the skin is smoother. These newts possess a prominent vertebral ridge, but no lateral grooves. The tail is laterally compressed with a rounded tip. Digits are shorter than in C. pyrrhogaster.

An unusually large female C. ensicauda popei.This long-lived species may get quite large. However, larger individuals have become scarce in the wild probably due to over-collection, especially in the southern part of Okinawa, where the average size has been getting smaller in recent decades. |

Sexual dimorphism

The female possesses a tail that is significantly longer than the rest of the body, whereas the tail of the male is the length of the rest of the body or slightly shorter. The cloacal region is usually enlarged in males, especially during breeding season. Cynops ensicauda males do not possess a tail filament or blue skin color during breeding season, as do other Cynops. Males of the nominate form, however, may display a whitish sheen on the sides of the tail during breeding season.

Male Cynops ensicauda ensicauda with white sheen on tail. |

Female Cynops ensicauda popei. Note that the tail is longer than the rest of the body. |

Coloration

The newts are brown to almost black on top. Newts of the popei subspecies generally tend to be a bit darker on top than the nominate form. The dorsal ridge may differ in color from the back and appear reddish to brown. Some individuals of both subspecies posess a yellow-orange dorso-lateral stripe of varying length, sometimes reaching from the eye to the base of the tail. This stripe may be disrupted into several dots or fragments. The belly is yellow to orange, occasionally red, with varying numbers of black dots or patterns that may be arranged in rows or spread irregularly across the belly. The belly color extends to the lower edge of the tail. In some individuals, the yellow of the underside may extend to the top parts of the feet as well as to parts of the trunk. The popei subspecies possesses light spots (often described as white, yellow, or golden) of various degrees on the dorsal and lateral parts of the body. In some individuals these spots condense to stripes and even completely "golden" individuals have been reported. These spots are absent in the nominate form, but some animals of this subspecies may show a fine white speckling on the back and sides. It is sometimes difficult to assign individuals to a certain subspecies just on the basis of coloration without any locality data, since some animals may display transitional traits. Dorsal colorations (light spots on popei as well as dorsal and dorso-lateral lines of both subspecies) are already observable in juveniles.

Ventral patterns in a group of Cynops ensicauda ensicauda. |

Ventral patterns in a group of Cynops ensicauda popei. |

Fine white speckling on a female of Cynops ensicauda ensicauda. |

Newly metamorphosed juvenile of Cynops ensicauda ensicauda. |

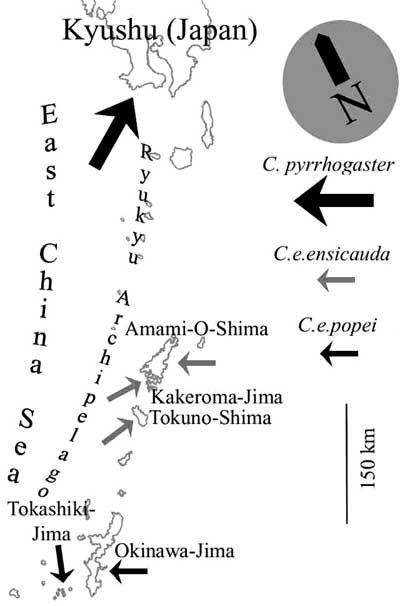

Map: Distribution of the two subspecies of Cynops ensicauda and the southernmost occurrence of C. pyrrhogaster .

Distribution and Natural Habitat

Distribution

Cynops ensicauda has a very limited distribution and occurs only on some of the southernmost islands of Japan, the Ryukyu Archipelago (called Nansei Islands by the Japanese). The nominate form inhabits different islands in the so-called Amami-group, specifically the islands of Amami-Ooshima, Kakeroma, Tokuno, Uke, and Yoro, which are all part of Kagoshima Prefecture. Cynops ensicauda popei can be found on the islands of Okinawa, Sesoko, Hamahiga, Tonaki, Tokashiki, Zamami, Geruma, and Aka, which are all administratively part of Okinawa Prefecture. However, some of the islands mentioned above are too small to be depicted in the following map. The status of Cynops ensicauda ensicauda on Tokuno is unclear at the moment, as it may have never lived there or has become extinct.

Habitat

Cynops ensicauda inhabits all kinds of water bodies with stagnant or slow-moving water. This includes natural ponds and streams as well as man made structures, such as rice paddies, road-side ditches, and cattle waterholes. These animals are sometimes very abundant in these water bodies during breeding season. Both adults and juveniles may also spend extended periods living terrestrially in woodland habitats.

Natural habitat of C. ensicauda popei

on Okinawa.

The islands of the Ryukyu Archipelago are characterized by a subtropical climate. This means that it is usually warmer, more humid, and more often rainy than in the temperate zones. This accounts for the relative tolerance of this species to higher temperatures, as compared to other genera or even other Cynops species. One population of Cynops ensicauda even has been found to live in water that occasionally reaches temperatures as high as 28°C (82°F). The following table provides an overview of some climatic characteristics of Okinawa. Looking at these data, one has to keep in mind that these are air temperatures and that temperatures in the water as well as in other micro-habitats, like leaf litter in the woods or shaded vegetation, may be lower.

Table: Long-term mean temperatures and rainfall on the

island of Okinawa, Japan.

(Based on information from http://de.weather.com,

database unknown.)

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Mean max. temp. | 18°C 64°F |

19°C 66°F |

21°C 70°F |

24°C 75°F |

26°C 79°F |

28°C 82°F |

31°C 88°F |

31°C 88°F |

29°C 84°F |

27°C 81°F |

24°C 75°F |

21°C 70°F |

| Mean min. temp. | 13°C 55°F |

14°C 57°F |

16°C 61°F |

18°C 64°F |

21°C 70°F |

24°C 75°F |

26°C 79°F |

26°C 79°F |

25°C 77°F |

22°C 72°F |

19°C 66°F |

16°C 61°F |

| Precipitation (mm) (inches) |

114 4.5 |

107 4.2 |

163 6.4 |

152 6.0 |

244 9.6 |

254 10.0 |

190 7.5 |

- - |

168 6.6 |

150 5.9 |

117 4.6 |

122 4.8 |

Threats to native populations

Almost no natural predators prey on these newts. Although this species often takes advantage of man-made habitats, it is nevertheless threatened by anthropogenic habitat alterations. Land development and deforestation on the Ryukyus have led to a decrease in the range of this species through habitat loss and deterioration of key habitats such as breeding sites. Observations on southern Okinawa have shown that breeding sites are frequented nowadays by just one fourth of the original breeding population compared to 15 years ago. Roads lead to a fragmentation of breeding populations, and a lot of terrestrially-living animals are run over by cars or end up in roadside ditches and gutters. Because of their shape, these ditches are often escape-proof concrete prisons in which almost all animals die of desiccation. Another peril is the large scale collection of mature animals for the pet trade and other purposes. Thus, locations with high densities of animals nowadays have to be kept secret.

Because of the threatened status of wild populations, it is strongly advised not to buy any wild caught animals through the commercial pet-trade, but rather to acquire captive bred eggs, larvae, or juveniles from fellow enthusiasts.

C. ensicauda popei in natural habitat. |

C. ensicauda popei in natural habitat. |

Captive care

Sword-Tailed newts are hardy and robust animals that can accompany their keepers for decades, if a few basic principles are obeyed.

Housing

Although observations in the wild indicate that adult sword-tailed newts may live terrestrially for long periods, they can be kept in a completely aquatic and densely planted setup or a semiaquatic setup with a large water area. The animals should be given the opportunity to rest above the surface using a small land area, floating plants, cork bark, driftwood etc. A tank measuring 60 x 30 x 30 cm (50 liters or 15 US gallons) is appropriate for two or three adult animals. Some bottom areas of the tank should be left unplanted for feeding purposes as well as potential areas for courtship behaviour. For more ideas on different setups, see: Setting It Up: Setup Ideas for Your Caudates.

When the animals are kept indoors in temperate zones, especially in centrally heated apartments and houses, no additional heating will usually be necessary. Although the animals tolerate water temperatures of up to 30°C (86°F) during summer, the best temperatures for them during most of the year is between 20 and 24°C (68 and 75°F). During the winter months, however, it is advised to lower water temperatures for at least 8 weeks to a range from 12 to 16°C (54 to 61°F) to stimulate breeding behaviour. A true hibernation or cool period below this range is not necessary. Larvae and juveniles do best at temperatures above 20°C (68°F). Like with other newt species, the water should be filtered and regular water changes should be made. One should also avoid creating a strong current by filtration. See also Aquarium Filters for Aquatic Caudates for the basics on filtration in caudate keeping.

In the wild, young sword-tailed newts do not return to the water until they reach adulthood. However, captive bred juveniles may be raised in different terrestrial or aquatic setups. Various methods are described below in "Breeding and rearing of offspring".

Adult aquatic setup with submerged plants,

bottom space for feeding and courtship, and emerging rocks and driftwood.

Cynops ensicauda popei in an aquatic juvenile setup. The island is cork bark overgrown with Java moss. |

Cynops ensicauda ensicauda in a terrestrial juvenile setup with moss. |

Feeding

Sword-tailed newts are not picky eaters, and a lot of different live and dead food organisms are accepted by the animals. One should keep in mind though, that the stalking and capture of prey is one of the most time-consuming activities for these animals in their natural surroundings. Feeding a variety of different feeds and occasionally live invertebrates may thus not only ensure the intake of appropriate nutrients, vitamins, and minerals, but also contribute to the animals' health by letting them exercise some very important facets of their natural behaviour. This species is easy to feed, and one of the least territorial or aggressive newt, which means that adults and juveniles of different ages can be kept together in groups. In this case one has to make sure, however, that all animals are feeding to prevent undernourishment of individuals.

Adult Cynops ensicauda have been found to feed on a wide variety of mainly invertebrate food organisms in the wild, including earthworms, small snails, insect larvae, and crustaceans, but occasionally also juveniles and eggs of their own species. In captivity, they will accept almost any common newt food like live earthworms (chopped if necessary), blackworms, white worms, scuds, and also dead food like frozen bloodworms, brine shrimp, mysis shrimp, or strips of lean beef heart or fish. For further information on food for newts, see Food Items for Captive Caudates.

Freshly hatched larvae don't have to be fed until they have used up their yolk sac. This usually happens within the first week after hatching, depending on water temperature. Appropriate food for the early larvae would be the smallest plankton available. In captivity, egg deposition with these subtropical newts often takes place in winter or early spring, when wild-caught plankton is not readily available. Thus, in temperate zones, it is often necessary to feed newly-hatched brine shrimp (Artemia nauplii). Subsequently, bigger food can be offered, such as microworms, moina, daphnia, white worms, blackworms, or tubifex. Older larvae may even accept frozen bloodworms. To introduce new food organisms (which holds true for other species as well) one should never switch foods abruptly, but rather feed mixtures of old and new feeds so that the animals can adapt to them. This way the animals will often learn to accept dead food as well just by texture, color, and smell. For further details on suitable small food organisms at his stage, see Microfoods for Caudate Larvae.

Metamorphosed juveniles can also be fed with tubifex, white worms, blackworms, and chopped earthworms according to their size. They can even be trained to accept frozen bloodworms from tweezers, or pick them up from a flat surface or lid. If the young newts are raised in a terrestrial setup, springtails (Collembola), aphids, flightless fruit flies, small crickets, termites, or small silverfish (Thermobia domestica) will be accepted as well.

Breeding and rearing of offspring

The animals reach sexual maturity at an age of 2 to 3 years, and males can mature up to 1 year before the females. According to some literature, the breeding season in the natural habitat starts in March and ends in July/August. There are indications, however, that breeding season may start as early as November in parts of this newt's range. Animals in captivity, however, show a general tendency to extend the breeding season, develop a second breeding season in fall, or even stay fertile for the whole year. Breeders of this species report egg laying throughout the whole year, with a peak from October to the end of June.

Courtship consists of the following phases:

1. Pursuit of the female. The male will suddenly be interested in the female and follow her around a lot throughout tank. During stops he will also nudge and sniff at her or even try to get in front of the potential partner especially when she ignores the male initially.

2. Tail-Fanning display. The male is positioned perpendicular toward the female's longitudinal axis and waves the end of his tail towards her. There are frequent breaks in fanning and, if the female is still moving away, phase 1 and 2 (Pursuit and Fanning) may be alternated rapidly.

3. Creep. The male lowers himself onto the bottom and slowly creeps away from the female looking into the same direction.

4. Deposition of spermatophore. After creeping the male deposits the spermatophore when he received tail touches by the female. He then pauses, slightly raises the tail and positions the spermatophore in front of the female.

5. Spermatophore pick-up.The female follows the creeping male on its path and positions her cloaca over the spermatophore, picking up the sticky sperm-cap.

Male (left) and female (right) C. e. popei in phase 2 (tail fanning).

More than one male may compete for one female, and attempts to take over a female by a different male during courtship have been described both in the wild and captivity.

No accounts of the number of eggs per female were found in the literature. From my own experience, there are individual differences, and older or larger females may lay up to 60 eggs per season. The eggs are sticky in the beginning and thus attached to submerged plants, grass hanging into the water in the wild, or even artificial substrates like plastic strings or strips in captivity. Females sometimes lay eggs on land in damp conditions close to the water; this has been reported both in the wild and in captivity. The reasons for this behaviour are unknown. The eggs are deposited singly by the female over a period of time (up to several weeks). Thus, one has to check frequently for new eggs, since the adults in the tank will eat them. Egg deposition takes place at night as well as during daytime. Eggs are approximately 3 mm in diameter and slightly oval. They are enclosed in a gelatinous sphere, with the egg and sphere together having a diameter of 4 to 5 mm (0.2 inch). Duration of embryonic development depends on water temperature and usually lasts from 12 to 18 days. Hatching larvae may reach a total length of 12 to 15 mm. Their length shortly before metamorphosis is usually 40 to 45 mm. However, batches of metamorphosing larvae between 50 to 65 mm (2 to 2.5 inches) length, and even larger individuals at the time of metamorphosis, have been reported from captive breedings. There also seems to be a correlation between the density of larvae in a tank and time of metamorphosis. The fewer larvae are kept together, the bigger and later they will go through metamorphosis.

Eggs of the two subspecies: popei on the left and nominate on the right. The white egg farthest to the right is dead. |

Egg developing on Egeria densa. |

Eggs should be separated from their parents if one intends to raise the young, since they are apt to be preyed upon by the adults. If hatched larvae reach the free-swimming stage in a densely planted adult setup, chances are good that these animals will survive. Several reports from different keepers indicate that older larvae are able to avoid being eaten by their parents.

During embryonic development prior to hatching, eggs can be kept in almost any bowl or container. Eggs that turn white during this period are dead and should be removed immediately to prevent the spread of fungus onto the healthy eggs. Aereation with a small membrane pump and an airstone seems favorable during this stage of development. What applies to the eggs holds true for the larvae as well. A small aquarium or transparent plastic container facilitates the control and observation of the larvae, and some submerged plants like pieces of Egeria provide cover for the larvae.

Young Cynops ensicauda ensicauda larva after hatching. |

Older Cynops ensicauda ensicauda larva. |

Depending on temperature, it takes the larvae from 3 to 6 months to develop into metamorphs. Findings from this species' natural surroundings suggest that juveniles lead a terrestrial life after metamorphosis until they reach sexual maturity, living and finding live prey in the marshes, grasslands, and vegetation in the vicinity of breeding ponds. In captivity, it is vital to provide possibilities for the metamorphosing juveniles to initially leave the water, as there is a high risk of drowning at this stage of development. This can be achieved by means of cork bark floats, the establishment of islands or land areas, or the lowering of the water level so that parts of tank bottom and structures break through the water surface. From this point on, the juveniles may be raised in different types of terrestrial setups. Some of the methods used by keepers are, for example, a paper towel setup, a setup with clay bricks, or setups using layers of moss. With these setups, it is important to maintain a certain level of humidity, without them being dripping wet. It is also important to provide cover or hideouts for the animals, and also rough surfaces to aid skin shedding. Soil used in such a setup has to be kept damp instead of wet. In a setup that is dripping wet, soil may foul easily.

However, it is also possible to raise this species in an aquatic setup, which also facilitates feeding and observation of the animals. For readapting the juveniles, one may leave them in the original setup with lowered water levels or transfer them to a new setup with a low water level of approximately 1 to 2 cm (roughly 0.5 to 1 inch) with lots of submerged plants (e.g. Java moss) or a small land area. This gives the animals the opportunity to rest with the head above water level and get used to living aquatically. Even new metamorphs may take to the water if given this possibility, but also older juveniles can adapt to an aquatic setup this way. As soon as the animals have adapted to this setup and start feeding underwater, the water level may gradually be raised.

When trying to get the animals used to living in the water again, one has to expect them to climb the sides of the tank a lot, so an escape-proof cover becomes very important. Animals that do not settle down and feed in the water after a couple of days should be removed and raised in a terrestrial setup. For further general information on the raising of newts, see Raising Newts from Eggs.

Cynops ensicauda ensicauda larva close to metamorphosis. Note that the animal looks a lot less like a larva and more like a newt, yet still has external gills. |

Cynops ensicauda popei juveniles shortly after metamorphosis. |

References

BACHHAUSEN, P., 2002: Die Feuerbauchmolche der Gattung Cynops, Part 1 - Haltung und Arten. Reptilia Nr. 38 December/January 2002/2003 (in German).

BACHHAUSEN, P., 2003: Die Feuerbauchmolche der Gattung Cynops, Part 2 - Nachzucht und Molchregister. Reptilia Nr. 39 February/March 2003 (in German).

CHAN, L.M., ZAMUDIO, K.R. & WAKE, D.B., 2001: Relationships of the Salamandrid Genera Paramesotriton, Pachytriton, and Cynops based on mitochondrial DNA sequences. Copeia 4: 997 - 1009.

DGHT (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Herpetologie und Terrarienkunde): Allgemeine Haltungsrichtlinien für Molche und Salamander (Schwanzlurche: Urodela) (in German).

FREYTAG, G.E. & BEUTEL, H., 1983: Morphometrisch-ökologische Untersuchungen an ostasiatischen Wassermolchen der Gattungen Paramesotriton, Cynops und Hypselotriton unter Berücksichtigung von Pachytriton (Amphibia, Caudata, Salamandridae). Zoologische Abhandlungen Staatliches Museum für Tierkunde in Dresden Bd. 38 Nr. 17, pp. 265-283 (in German).

HAYASHI, T. & MATSUI, M., 1988: Biochemical differentiation in Japanese newts, Genus Cynops (Salamandridae). Zoological Science 5: 1121 - 1136.

INGER, F.R., 1947: Preliminary survey of the amphibians of the Riukiu Islands - Fieldiana: Zoology 32(5): 297-352.

JOHNSON, T., 2002/2003: Personal communications on Cynops ensicauda. Writer/Photographer/Researcher, Tokyo, Japan.

JOHNSON, T., 2004: Observations of Cynops ensicauda popei habitats in the subtropical rainforests of Yambaru, Okinawa, Japan. Caudata.org Magazine 1: 7-25. Available online at https://www.caudata.org/magazine/caudata_magazine_issue_1.pdf

MASURAT, G. & GROSSE, W.R., 1991: Lurche; Vermehrung von Terrarientieren.Auflage Jena/Berlin p. 164 ISBN 3-332-00270-8 (in German).

RIMPP, K., 1978: Salamander und Molche: Schwanzlurche im Terrarium. Eugen Ulmer GmbH & Co, Stuttgart p 205 ISBN 3-8001-7045-0 (in German).

SPARREBOOM, M. & OTA, H., 1995: Notes on the life history and reproductive behaviour of Cynops ensicauda popei (Amphibia: Salamandridae). Herpetological Journal 5: 310-315.

SPARREBOOM, M. 1998: Maintenance and breeding of newts of the genus Cynops. British Herpetological Society Bulletin 63: 3-12. Text available online at Caudata.ru via archive.org.

SPARREBOOM, M., 1996: Sexual interference in the Sword-tailed Newt, Cynops ensicauda popei (Amphibia: Salamandridae). Ethology 102: 672-685.

THORN, R. & RAFFAELLI, J., 2001: Les Salamandres De L'Ancien Monde (in French). Societe Nouvelle des Editions Boubee p 449 ISBN - 2-85004-104-1.

© Ralf Reinartz, 2004. Posted January 2004. Revised October 2004.