| Neurergus kaiseri | |||||||||||

| Kaiser's Spotted Newt | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Update Effective March 22, 2010, Neuergus kaiseri has been listed as CITES Appendix I. For discussion, see forum thread.

Description

Neurergus kaiseri is the smallest of the Neurergus species, with an adult length of 10-14 cm. Sparreboom et al. (1999) describe the coloration of this species as "unique and rich in contrast, with a mosaic of black and white patches and orange-red dorsal stripe, legs and belly."

The sexes can be differentiated by the anatomy of the cloaca, with the male having an enlarged, rounded cloacal region, and the female having a volcano-shaped cloaca. However, these differences are clearly visible only during the breeding season. Outside of the breeding season, it may be impossible to distinguish between the sexes.

The morphology of the skull and vertebrae reveal significant differences between N. kaiseri and N. strauchii, but greater similarity between N. kaiseri and Triturus alpestris. Evolutionary analysis based on DNA reveals that the 4 Neurergus species are monophyletic (a single lineage), and their nearest relatives are the Triturus and Euproctus.

|

|

Natural Range and Habitat

N. kaiseri are native to the Luristan Province of Iran, at an altitude of 750-1200 m (2400-4000 ft). Unlike the other Neurergus, which live in cold climates and inhabit cold mountain streams, N. kaiseri come from a hot dry climate. They reproduce in winter during periods of rain, which are followed by long periods of hot dry weather in which the animals estivate. It is estimated that water is present in their habitat for 3 months of the year or less. Unlike the other Neurergus, N. kaiseri are reported to use ponds and vernal pools, in addition to streams. However, their wild habitat has not been well studied.

Conservation Status

As of 2005, the IUCN Redbook listed N. kaiseri as Critically Endangered. The Global Amphibian Assessment cites the following evidence: "its extent of occurrence is less than 100 km2, its area of occupancy is less than 10 km2, its populations are severely fragmented, and there is a continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat, as well as a decline in the number of mature individuals due to overharvesting for the illegal pet trade". It is believed that less than 1000 adults exist in nature.

In light of the endangered status of these animals, it is critically important that the animals now in captivity be bred, and that hobbyists resist the temptation to buy wild-caught animals. We hope that this caresheet will help in the establishment of stable captive breeding groups. We encourage all breeders to participate in studbooks and to correspond with other breeders.

|

|

Behavior and history in captivity

N. kaiseri have a reputation for being a shy, skittish species. Their movement on land resembles that of lizards more that that of typical salamanders. When aquatic, however, the animals usually lose their flighty behavior and may even beg for food. Wild-caught adults are generally more shy than their captive-bred counterparts. The animals generally avoid light and are active in low light and at night.

When terrestrial, the newts spend the day under the lower hides and at night will forage for food amongst upper hides and open spaces. They have a preference for perching high and are very active soon after the lights are turned out. The water dish is used frequently and the animals are often seen taking a quick soak. They are very gregarious towards one another and will often be found huddled together under a single hide. Intraspecific aggression is not a problem.

The first known captive specimens of N. kaiseri were brought to Europe from field studies conducted in 1970s by father and son Schmidtler and Schmidtler. In the early 1990s, Schultschik and Steinfartz brought some pairs to Europe, from which some descendents are still alive. In recent years (2005-2008) there have been illegal exports of N. kaiseri from the wild into the pet trade. Given the endangered status of the species, it is likely that this distribution of wild-caught animals has had a serious impact on wild populations. Many of these wild-caught animals have died from infections within a short time after purchase. Even before these illegal exports began, there was a studbook maintained by AG Urodela in Germany. It was not very successful, as many CB F1 animals died in captivity. However, some F2 animals have been produced, and studbooks should be maintained to ensure the continuation of the animals now in captivity.

Setup for aquatic housing of N. kaiseri

Housing

The housing needs of N. kaiseri are similar to those of other newts that migrate seasonally between land and water. When kept aquatic, most keepers opt for a large semi-aquatic setup containing plenty of rocks and hides, both above and below water. Water level can be deep, with levels of 20-30 cm (8-12 in) being typically used. It is unclear whether or not these animals utilize swiftly-moving water in the wild. Thus the filter should produce no more than gentle movement of the water in the tank.

For periods of terrestrial housing, most keepers opt for a soil-based substrate kept on the dry side. The enclosure should be furnished with plenty of stacked rocks or bark. Setups for this species do not need to be misted, and excess moisture may be detrimental. It is recommended that a moisture gradient be provided in the soil by adding water to only one end of the setup. A shallow water bowl provides insurance against drying out, and the animals will often use it. The crevices between the pieces of rock or bark provide the animals with a full range of moisture options and hiding places. Bricks with holes in them are also very appropriate, for both aquatic and terrestrial habitats.

Temperatures of between 15-25°C (60-68°F) are appropriate, although this species can tolerate temperatures up to 30°C (86°F) when housed on land. During winter, terrestrial animals have been kept down to near-freezing temperature without ill effect, although this is not recommended due to the risk of freezing. Even at temperatures approaching freezing, the animals remain active and feed. A cold (5-10°C; 40-50°F) terrestrial period in late autumn and early winter seems to stimulate breeding, as is the case for N. strauchii.

Appropriate housing for N. kaiseri during the summer months is a much-debated topic. In the wild, to the best of our knowledge, these animals spend the summer in hot dry habitat with little or no access to water. Their water source normally dries up and they have no choice but to estivate for many months on land. Thus, many keepers believe that it is important to keep the animals fully terrestrial outside of the breeding season. Some believe that it is important to replicate their normal yearly cycle as closely as possible and that the terrestrial phase helps to prepare the animals for breeding. In contrast, other keepers report successful housing and breeding of animals that have been kept fully aquatic all year round. However, not enough breedings have been reported to say conclusively what effect terrestrial versus aquatic housing has on breeding. In most cases, kaiseri never "choose" to move from the water to the land portion of the tank at any time. (This is in contrast to some newt species, such as Triturus, in which most adults will voluntarily move to the land portion of the tank in summer.)

Setup for terrestrial housing of N. kaiseri

Feeding

Terrestrial adults and juveniles are fed small earthworms (whole or chopped), lesser wax worms, large fruit flies, maggots, tropical woodlice, and crickets of appropriate size. When aquatic, they can be fed the usual assortment of newt foods, such as earthworms, live/frozen bloodworms, etc. They are not picky eaters.

Breeding

A winter cooling period is essential for breeding. The exact temperature and length of time needed to elicit breeding is not known. Although the native habitat of N. kaiseri is generally hotter than that of the other Neurergus, most successful captive breedings have been achieved under conditions nearly identical to those used for N. strauchii. Sparreboom et al. (1999) reported courtship behavior after a winter cooling at 17°C and introduction of the animals into water in February. However, Bogaerts reports that he was unable to breed them under these conditions; the females were gravid, but the males did not come into breeding condition. Better success was achieved when the animals were kept below 10°C (50°F) for a few weeks. Alan Cann has had breeding success with a winter cooling period at 8-15°C (46-59°F). Most breeders keep the animals in a place where they receive natural light or artifical light that mimics the natural photoperiod. For animals that are cooled under terrestrial conditions, the animals should be warmed up to spawning temperatures slowly, over several days. Feed generously and allow them to enter the water for spawning when they are ready. They will usually enter the water very quickly.

Unlike the other Neurergus species, N. kaiseri have been observed breeding in stagnant pond-type environments. Although they inhabit still water in the wild, captive breeding has generally taken place in aquariums that have some gentle water flow.

Courtship behavior generally resembles that of Triturus. Facing the female, the male fans his tail, attempting to maintain his position in front of her. In contrast to the other Neurergus, only the distal third of the tail is fanned. The male then turns away from the female and deposits a spermatophore in front of her. He then moves one body length forward and turns to block her path. If she is receptive, she advances and picks up the spermatophore with her cloaca.

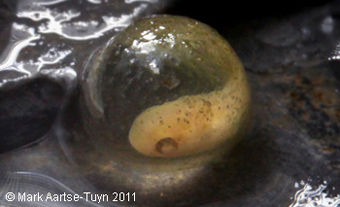

N. kaiseri eggs are larger than the eggs of other Neurergus species. In nature, eggs are deposited singly on rough surfaces. Unlike other Neurergus, which ordinarily lay eggs on the underside of stones, kaiseri also use vegetation for laying their eggs. The eggs are laid away from light, but not always on the underside of stones. In captivity, eggs are deposited in many different locations in the tank - on stones, rocks, plants, glass - and many are laid in illuminated areas.

|

|

|

|

Care of Eggs, Larvae, and Juveniles

Eggs are normally incubated at a similar temperature to that at which they were laid. The larvae are easy to raise and do not ordinarily encounter problems. It is important to feed the larvae Daphnia, Gammarus or other crustaceans in order for them to develop the species' normal orange-red coloration after metamorphosis. Metamorphosis can be slow, with the juveniles sometimes attaining adult coloration before loosing their gills.

At metamorphosis, the animals may move to land. Juveniles can be raised in terrestrial setups, arranged as described above. Bogaerts also reports raising them in an aqua-terrarium without problems. Even if they are kept terrestrially, they will often enter water to search for food. Juveniles are generally robust and hardy, with very good appetites. They can grow very quickly, with well-fed juveniles doubling in size in only a few months. In captivity, animals reach breeding size at 2-3 years of age.

N. kaiseri eggs |

N. kaiseri embryo |

N. kaiseri larva, approximately 5 weeks old |

N. kaiseri larva, approximately 3 months old |

References

Bogaerts, Serge. Personal communication.

Cann, Alan. Personal communication.

Global Amphibian Assessment: Neurergus kaiseri. http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/59450

Rastegar-Pouyani, Nasrullah (2003). FrogLog 56: Ecology and Conservation of the Genus Neurergus in the Zagros Mountains, Western Iran. Declining Amphibian Populations Task Force. http://www.amphibians.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Froglog56.pdf

Schultschik, G, and Steinfartz, S. (1996) Ergebnisse einer herpetologischen Exkursion in den Iran (Results of a herpetological excursion to Iran). Herpetozoa 9:91-95.

Sparreboom, M, Steinfartz, S, and Schulschik, G (2000) Courtship behavior of Neurergus. Amphibia-Reptilia 21: 1-11.

Steinfartz, S, Hwang, UW, Tautz, D, Oz, M, and Veith, M (2002) Molecular phylogeny of the salamandrid genus Neurergus: evidence for an intrageneric switch of reproductive biology. Amphibia-Reptilia 23: 419-431.

Additional Resources

AmphibiaWeb page on Neurergus kaiseri

©2008 Caudata Culture. Posted February 2008. Contributors: Mark Aartse-Tuyn, Serge Bogaerts, Alan Cann, Coen Deurloo, and Morg. Compiled by Jennifer Macke.