| Pachytriton brevipes Pachytriton granulosus | |||||||||||||

| Paddletail Newt | |||||||||||||

Pachytriton labiatus. |

|

||||||||||||

Taxonomic Note

At the time this sheet was written, the common pet-trade variety of paddletail newt was named Pachytriton labiatus. As of 2013, there have been many changes in the taxonomy of Asian salamanders. It appears that the former Pachytriton labiatus are Pachytriton granulosus and/or Pachytriton inexpectatus. Some of the formerly undefined species (A, B, C, D) have turned out to be members of genus Paramesotriton.

Description

Pachytritons are stout-bodied, smooth-skinned aquatic newts. Their heads are large and flattened, and the tails are laterally compressed, broad, and rounded at the end. They have conspicuous labial folds (overhanging lips, giving them a fish-like gape) and short stubby legs and toes. Respiration is accomplished through both lungs and skin. Among the Asian salamanders, the Pachytritons have the fewest primitive characteristics. They are the most environmentally specialized and are considered evolutionarily advanced in comparison to Cynops, Paramesotriton, and Tylototriton.

These newts are sometimes mistakenly sold as "Fire Belly" or "Giant Firebelly" newts. Other species, such as Paramesotriton, are occasionally sold as "Paddletail Newts". (See: What Kind of Firebelly Is It?) Knowing your newt's true identity is very important to its captive care. The most important features of Pachytritons that distinguish them from other "firebellies" are their aggression and exclusively aquatic lifestyle.

There are two Pachytriton species officially described at the time of this writing: Pachytriton brevipes and Pachytriton labiatus. Average adult length (nose to tail) for both species is 6-7 inches (15-18 cm). Due to the confusion surrounding the other species in the Pachytriton complex, this care sheet is only intended to cover these two species:

Pachytriton brevipes is a medium brown, smooth skinned newt with numerous black spots speckling the body. The venter is less colorful than that of most P. labiatus. It ranges from spotted to pale yellow or orange patches mixed in with the dorsal color. Adult males of breeding age can develop white tail spots, but they are less defined and less bold than those of P. labiatus. P. brevipes is more likely to show up in the European market, although some occasionally show up in the American pet trade.

Male P. brevipes

Pachytriton labiatus is the newt most commonly sold as a "Paddle Tail Newt". The body is normally a dark brown, although paler specimens appear from time to time. The venter ranges from brown and red mottling, to a mosaic of brown, red, and white. Sometimes the red is more of an orange color. Adult males develop bold white spots on their tails when in breeding condition. Both males and females can have a row of red spots or stripes along their sides and tails.

P. labiatus

In addition to these two species, there is also a complex of additional Pachytriton species that have not been formally named. These newts come from unknown locales and are only known from animals imported in the pet trade. Four of the species that make up this complex are currently referred to as Pachytriton A, Pachytriton B, Pachytriton C, and Pachytriton D. There is intent to formally name these species once the collection locality of these newts has been determined. Despite their popularity as pets, there is little hard data on these newts, and many unknown types and new species show up in the pet trade.

Natural Range and Habitat

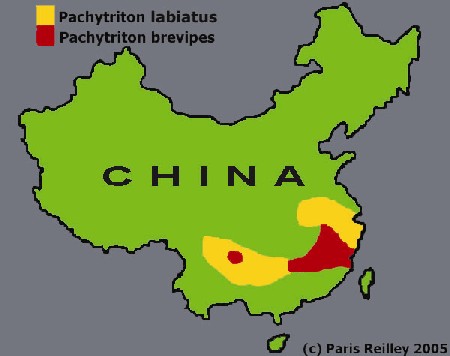

Pachytritons are native to central and southern China. Both P. brevipes and P. labiatus are highly specialized to living in clear, swiftly flowing, highly oxygenated, streams. Their distribution in their range is small but continuous, leading to the assumption that they are a relatively new genus.

Range map of Pachtriton species.

Data from Zhao and Hu, 1988.

Housing

A fully aquatic setup is recommended; one that mimics their natural habitat is best. Temperature below 65°F (18°C) is best, but they can tolerate the low 70's °F (21-24°C) for short periods of time. Water must be deep enough to cover the entire animal at a minimum, but based on personal observation, deeper water is recommended for better health and comfort. A minimum volume of 5-10 gallons (20-40 liters) per newt is fine with adequate filtration. Substrate, if used, must be fine sand or gravel larger than what the newt could swallow; they are very eager eaters and can easily suck up substrate with their meal. Water should be kept clean and preferably aerated and moving: canister, box, submersible, and undergravel filtration all work well. Activated charcoal and ammonia absorbing resins are available for use in all of these systems. Sponge filters and bubble stones are less effective at maintaining water quality and require more water changes. A partial water change of 10-20% is recommended weekly, regardless of filter type.

These are hearty newts and can tolerate poor conditions, like those at pet suppliers, for some time. However, extended periods of poor conditions will invariably compromise their health. Stream-dwelling amphibians are typically sensitive to toxins and pH fluctuations and prefer cool water with plenty of dissolved oxygen. Kept properly, these newts make good captives and can live for many years. Although longevity data are lacking, I have had one of my adults for 9 years at the time of this writing.

Pachytriton need hiding places, such as flower pots and propped rocks. Newts shown are likely Pachytriton "D". |

P. labiatus |

P. labiatus. |

P. labiatus. |

Cage decor can be kept to a minimum, but at least one hiding spot should be available to each newt, and additional visual barriers such as plants will allow different places to retreat to prevent intraspecies aggression. Common items used for refugia include sections of PVC pipe, decorative items made for fish, clay flower pots, and flat rocks propped up by a stone. A tight lid should be kept on these newts; they can use their powerful tails to jump out of water. Although these newts rarely climb, the possibility should not be ruled out.

If a Pachytriton rests constantly at water level, or comes out of the water, there is something wrong. Any paddletail exhibiting such behavior should be watched closely for signs of disease or bullying by tankmates. A floating platform or floating plants should be offered for sick or weak newts.

These newts SHOULD NOT be kept with any other species. Some people have reportedly kept them in with other newt species without problems "until one day..." I can personally report that they are able to rip the legs off an adult tiger salamander. Any fish kept with them is likely to be mutilated or eaten.

Pachytriton, probably species "B". These newts should NOT be kept with any other species. |

Pachytriton, probably species "B". |

Captive Behavior

P. brevipes and P. labiatus originate from oligotrophic (low-nutrient, oxygen-rich) rivers. In such environments, food is scarce, and they deal with this by establishing a territory and exhibiting aggression towards others of their kind. These are highly aggressive newts, and should not be kept with other species. If the tank is small, they should not even be kept with others of their own kind. Bite marks can be seen as curved shape marks on the skin or even missing limbs. Bites can be fatal, sometimes even killing both animals.

Of the two species, P. labiatus is the more aggressive. Male P. labiatus will attack others who flee from them. Females will also attack males and any other females they can push around. A male and a female will not necessarily get along. They may do fine for some periods of time, but then attack each other during feeding frenzies. Aggression is especially high in breeding season. If you do keep a breeding pair, give plenty of hiding spots, and if possible feed at different ends of the tank or hand feed to avoid bites.

P. brevipes can be housed in small groups, providing they each have their own territory (hiding place). However, aggression can still be seen in them during feeding and territorial disputes. When introducing a new tankmate, it is suggested to change the setup of the entire tank so they both need to establish "new territory".

Males of both species are fond of very plump females and will accept them better than thinner females. Males will tolerate females who ignore them, but ones that flee will be chased and attacked. Well-settled Pachytritons will be seen moving about the tank and not aggressively chasing or hiding from each other. If it is found that if one animal is loosing weight, has repeated bite marks, or is constantly out on a land or up at the water level, moving them to separate tanks may be the only solution.

Pachytritons are known for their chemical communication. Tail fanning at all times of the year is one distinctive trait exhibited by both sexes, and this behavior is not always associated with mating. Males will fan wildly when trying to get a female"s attention, and both genders will moderately fan when approached by others, or when disturbed. Light tail nipping by females is harmless and flirtative. If, however, one is seen to constantly follow another"s tail and bite it, this is a form of aggression.

Some Pachytriton from the pet trade carry aquatic external parasites (mites). These are dark brown and are usually found between the toes, in arm/leg pits, near vents, and even along the large vein behind the arms. These are harmless in small amounts, and can easily be removed with tweezers.

P. brevipes |

P. brevipes |

P. brevipes |

P. brevipes |

P. brevipes |

P. brevipes |

Feeding

Pachytritons are voracious eaters, though some have definite food preferences. Worms, insects, frozen bloodworms, beef heart, fish, dry food pellets, and even small amounts of lean meat are readily consumed. I have found that one of the species I keep, possibly Pachytriton B, has a preference for live fish, but P. labiatus does not. Food is consumed by buccal pump (suction). Items offered should be of a size that is easy to swallow, as larger items are likely to be fought over. Uneaten food should be promptly removed from the tank to preserve water quality.

Pachytriton, probably species "D". |

Pachytriton, probably species "D". |

Pachytriton, probably species "A". Spots on the tail indicate that this is a male. |

Pachytriton, probably species "D". |

Breeding

Sexing of these newts is fairly easy when they are in breeding condition. A male will have swollen cloaca, and papillae (2-mm hair-like structures) may protrude from it when excited. It is easier to identify an adult male than a female or a juvenile male, because they will have white spots on the last 1/3rd of the tail. During breeding season these spots are bolder, but they can be visible year round. This is more pronounced in P. labiatus than in P. brevipes. Outside of breeding condition, the head-to-body width ratio and vent length can be used somewhat reliably. Males have longer vents than females. In respect to body, the head width of an adult female (of good weight) will appear to be less than or equal to the torso width when viewed from above. Adult males have larger heads and leaner bodies, so their heads look wider in relation to the body when viewed from above.

Courtship for P. labiatus is similar in some ways to Cynops. It consists of a male approaching a gravid/plump female and fanning his tail vigorously at her. Either gender may nudge the other, especially at the cloaca, to test the other"s receptiveness. If she doesn"t turn away, the male will stand before her and keep fanning. If the female walks away, he will move ahead of her to block her path. When the female stands still, the male will turn and walk away from her, undulating his tail in ever tightening waves. If the female is receptive, she will take interest in the male"s tail and touch it with her nose or nip at it while he walks forward. The nose/tail touching will continue until his tail is folding in very tight curves. At this point, her touch or nip will clue him to rise up his tail to deposit the spermatophore on the substrate. After deposition, the male walks slowly forward while still tightly folding and undulating the tail; the female walks behind still following the tail. When her cloaca passes over the spermatophore, it will stick, and she will absorb the sperm.

I have witnessed courtship in my P. labiatus, and I have seen spermatophores produced by both species, but have not had any eggs produced in the last 5 years. Actual reproduction of these newts in captivity is a rare occurrence, and little data is known. A few European keepers have gotten results by keeping males separate from females during the winter cooling period and introducing them to each other in February or March.

Records of clutches of about 40 eggs are reported for P. labiatus. The female lays the eggs on the ceiling of excavated or cave-like structures. She actively guards the eggs during their development.

Female P. labiatus guarding her eggs. |

P. labiatus eggs, the result of a rare captive breeding. |

References

Duellman, W, et al. 1999. Patterns of Distribution of Amphibians, a Global Perspective. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore,USA.

Duellman, WE, & Trueb, L. 1986. Biology of Amphibians. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, USA.

Larson, A. Tree of Life: Salamandridae.

http://tolweb.org/tree?group=Salamandridae

Accessed January 8, 2005.

O'Reilly, JC, Deban, SM, & Nishikawa, KC. 2002. Derived Life History Characteristics Constrain the Evolution of Aquatic Feeding Behavior in Adult Amphibians. Topics in Functional and Ecological Vertebrate Morphology, pp. 153-190. Available online at http://autodax.net/debancv.html

Spareboom, M, & Thiesmeier, B. 1998. Courtship Behavior of Pachytriton labiatus (Caudata: Salamandridae). Amphibia Reptilia, pp. 339-344.

Wallays, H. New species of genus Pachytriton. Formerly available at http://www.caudata.ru/henk/hwpage.files/pach_c.htm.

Accessed January 1, 2005.

Wright, KM, & Whitaker, BR. 2001. Amphibian Medicine and Captive Husbandry. Krieger Publishing Company: Florida USA.

Zhao, E, & Hu, Q. 1988. Studies on Chinese Salamanders. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles: Ohio, USA.

© 2005 Paris Reilley