| Plethodon glutinosus complex | |||||||

| Slimy Salamanders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

Description

The slimy salamander complex is a group of large eastern woodland salamanders, with adults commonly reaching lengths of up to 6.75 inches (17 cm). Depending on the author, there may be as few as three species (Petranka, 1998) or as many as thirteen different species (Conant and Collins, 1991). However, the species are generally indistinguishable in the field. The only way to tell the species apart (except for chromosomal analysis) is to know the locality origin of each salamander. For the purpose of this article, the different species can all be treated as the same species.

Slimy salamanders to me are somewhat misnamed, as a better name would have been sticky salamanders. The first time you try to restrain one with your bare hands is a memorable experience. The salamander will coat your hand in a seemingly never-ending supply of thick, sticky mucous that is very difficult to remove by washing. My first attempt to catch one by hand resulted in my having to spend about 10 minutes scrubbing the mucous off with sand in a nearby stream.

Natural Range and Habitat

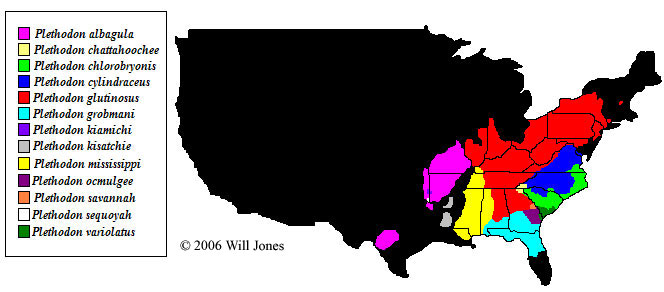

The slimy salamander complex can be found inhabiting most of the eastern United States from Connecticut south to Florida and west to Oklahoma and Missouri. The actual locations may somewhat disjunct due to available habitat. The preferred habitat of the slimy salamander complex is moist undisturbed woodlands and moist wooded ravines. During the day, the salamanders will be located under logs, stones, and other forest floor debris, as well as in burrows. At night, after rains, or during humid moist weather, the slimy salamanders can be located while foraging for food above ground. During hot and dry weather, the salamanders will seek shelter underground in burrows, caves, in or under fallen logs, and in rock crevices.

The following diagram shows the approximate ranges of the species of slimy salamanders. For precise range information, please consult current published guidebooks or information available locally.

| Species | Common name | Range | IUCN Red Book | CITES | First described |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plethodon albagula | Western Slimy Salamander | USA: southern Missouri, northern and western Arkansas, northern and central portions of eastern Oklahoma and south-central Texas | Least Concern | No listing | Grobman, 1944 |

| Plethodon chattahoochee | Chattahoochee Slimy Salamander | USA: Chattahoochee National Forest in northern Georgia and southeastern Cherokee County, North Carolina | Least Concern | No listing | Highton, Maha & Maxson, 1989 |

| Plethodon chlorobryonis | Atlantic Coast Slimy Salamander | USA: southeastern Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and northeastern Georgia | No listing | No listing | Mittleman, 1951 |

| Plethodon cylindraceus | White-spotted Slimy Salamander | USA: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and eastern West Virginia | Least Concern | No listing | Harlan, 1825 |

| Plethodon glutinosus | Northern Slimy Salamander | USA: Kentucky, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, New Jersey, Connecticut, New York, and New Hampshire | Least Concern | No listing | Green, 1818 |

| Plethodon grobmani | Southeastern Slimy Salamander | USA: southern Alabama and southern Georgia south to central Florida | Least Concern | No listing | Allen and Neill, 1949 |

| Plethodon kiamichi | Kiamichi Slimy Salamander | USA: Polk County, Arkansas and LeFlore County, Oklahoma | Data Deficient | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon kisatchie | Louisiana Slimy Salamander | USA: northern Louisiana and south-central Arkansas | Least Concern | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon mississippi | Mississippi Slimy Salamander | USA: southwestern Kentucky south through western Tennessee, eastern Mississippi, western Georgia and southeastern Louisiana | Least Concern | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon ocmulgee | Ocmulgee Slimy Salamander | USA: Central Georgia associated with the Ocmulgee River drainage | No listing | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon savannah | Savannah Slimy Salamander | USA: Burke, Jefferson, and Richmond counties in Georgia | Least Concern | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon sequoyah | Sequoyah Slimy Salamander | USA: Oklahoma and Arkansas | Data Deficient | No listing | Highton, 1989 |

| Plethodon variolatus | South Carolina Slimy Salamander | USA: South Carolina | No listing | No listing | Gilliams, 1818 |

Plethodon albagula, Western Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon albagula, Western Slimy Salamander |

Captive Care and Housing

Slimy salamanders should be kept in a cool area such as a temperature-controlled room or a basement. The temperature should not be allowed to rise above 76°F (24.4°C) as stress and potential death can result. If possible, the salamanders should be kept at a cooler temperature as opposed to a warmer temperature, as there is some evidence that salamanders kept at cooler temperatures are better able to resist sudden increases in temperature (Sealander and West, 1969). Cycling of the temperatures for breeding should be accomplished slowly, preferably not varying the temperature more than one degree per day.

Plethodon cylindraceus, White-spotted Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon glutinosus, Northern Slimy Salamander |

Slimy salamanders can be easily maintained in plastic shoeboxes or sweater boxes lined with moistened unbleached paper towels. The shoebox or sweater box should have several crumpled paper towels, in addition to the ones lining the bottom, for the salamanders to use as shelter. This will help alleviate any stress the animal may be undergoing. Unbleached paper towels have several advantages for use besides ease of cleaning. They serve as a suitable parasite and pathogen free substrate for animals undergoing a quarantine period. Additionally, the towels serve as an excellent substrate for monitoring the success of courtship by allowing the easy detection of spermatophores. The paper towels should be changed at least once a week and preferably no more than twice a week, as cleaning too frequently may stress the salamanders and depress feeding activities (Jaeger et al., 1981). Care must be taken to prevent the escape of the salamander, so tight fitting lids are required. Several small holes can be drilled at each corner of either the lid or shoebox to facilitate air exchange. For long-term maintenance, the salamanders can also be set up in terrariums.

Slimy salamanders will burrow if the substrate is soft enough. A substrate of finely milled cypress mulch or fertilizer-free soil is adequate for long-term maintenance. The substrate can be packed down to prevent the salamanders from burrowing and to allow for easier observation. The substrate should be maintained slightly moist without any standing water; if water can be easily squeezed from the substrate, the substrate is too moist and will readily sour leading to unsanitary conditions. With slimy salamanders, there should not be any deep standing water either in a bowl or in the terrarium itself, as the salamander may possibly drown. There should be enough cover objects to allow each salamander to stake out its own territory to help minimize aggression between the salamanders. Suitable cover objects can consist of commercially available hide boxes, cork bark, or flat pieces of inert stones such as slate. The space under the cover objects should not be lined with sphagnum moss or other acidic substrates as many plethodontid salamanders show a preference for retreats with a substrate as close to a neutral pH as possible (Bille, 2000). For similar reasons, peat moss is unsuitable as a substrate for slimy salamanders. When red-backed salamanders (Plethodon cinereus) were kept on a substrate with a low pH, the salamanders had problems maintaining water balance and sodium levels, causing unnecessary stress. Keeping the salamanders on a substrate with a pH of 4 or less for extended periods has also been shown to be lethal (Bille, 2000). If there is any question as to whether a substrate is too acidic, add some substrate to distilled water, and test the pH of the solution. If possible, allow the solution to sit for at least 24 hours and read the pH using a pH probe. If a pH probe is unavailable, allow the solution to settle and pour off the liquid. The liquid can then be tested with a pH test kit suitable for aquarium use.

Plethodon grobmani, Southeastern Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon kiamichi, Kiamichi Slimy Salamander |

If there is a need to disinfect the enclosure, all organic materials such as wood and mosses should be disposed of while the enclosure itself, hide boxes, water bowls, and all stones can be treated with a bleach solution (Wright, 1993; Wright, 1994; Rossi and Rossi, 1994). After rinsing the items in the bleach solution for 15 minutes, rinse in fresh water until no odor of bleach is present and allow to air dry. Alternatively, the items may be rinsed in a commercial aquarium dechlorinator and then allowed to air dry (Recios, 2001). One of the benefits of disinfecting with bleach is that all pheromone markers will be removed, allowing introductions to be conducted in the enclosures without having established territorial markers being present. No iodine-based cleaners should ever be used on amphibian enclosures, as toxic residues may remain (Wright, 1994).

The stocking density of the enclosure will vary depending upon the size, sex, and age of the salamanders. Sexually mature males will require a larger territory than females or juveniles. When introducing salamanders together to form a colony, the salamanders need to be monitored for injuries, particularly to the nasolabial groove. Injuries to the nasolabial groove can inhibit the salamanders ability to feed as well as court female salamanders. Unless the injury is exceptionally severe, the damage will eventually heal. There are some indications that Plethodontid salamanders may be more aggressive to conspecifics in captivity than in the wild due to the offering of richer food items such as crickets. Some Plethodontid salamanders have been shown to more aggressively defend territories that are richer in termite prey than those territories in which ants are more prevalent, as the termites are a more nutritious food item (Gabor and Jaeger, 1995; Townsend and Jaeger, 1998; Gabor and Jaeger, 1999). During introductions, care must be taken to not place salamanders with a large size difference together, as the larger salamander will prey upon the smaller individual. In addition, if breeding of the slimy salamanders is intended, then housing slimy salamanders with Jordan's salamanders (Plethodon jordani), Tellico salamander (Plethodon aureolus), and Cumberland Plateau Salamander (Plethodon kentucki) is contraindicated, as these species may potentially hybridize with slimy salamanders (Petranka, 1998). Another potential hybridization concern would be the housing of slimy salamanders from disparate localities. If possible, only salamanders of the same locality should be housed together to avoid possible hybrids. I have had good success with a stocking density of two males and three females in a 10-gallon aquarium. Preference should be given towards enclosures that allow for more floor space over vertically oriented enclosures as the salamanders will not use the vertical space as readily.

Plethodon mississippi, Mississippi Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon ocmulgee, Ocmulgee Slimy Salamander |

Adult slimy salamanders may be fed 10-day-old crickets (Acheta domestica), fruit flies (Drosophilia spp.), small redworms (Lumbriculus spp.), and small waxworms (Galleria mellonella). Newly hatched slimy salamanders can be fed white worms (Enchytraeus sp.), springtails (Collembola sp.), and pinhead crickets. As the juveniles grow, larger prey items can be added to the diet. Care must always be taken not to stress the salamanders by the addition of too many food items. Not only will the prey items die and pollute the cage, but the crickets may actually prey upon the salamander if present in excessive numbers. If possible, all food items should be dusted with an appropriate vitamin supplement. The temperature will determine the frequency of feeding; twice a week feeding is sufficient at 65°F (18°C). Depending on the food being offered, the amount required will vary. Approximately 10-15 ten-day old crickets per adult salamander per feeding is a good starting ratio. If there are excessive numbers of food items left in the enclosure the following day, the number of food items should be decreased as needed. If there is a concern that too little food is being offered, the salamanders can be weighed each month to test for weight loss. If there is a total loss in weight, equal to 10% or more in one month or over several months, then either the frequency or number of food items offered may be increased.

Plethodon savannah, Savannah Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon sequoyah, Sequoyah Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon chlorobryonis, Atlantic Coast Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon chattahoochee, Chattahoochee Slimy Salamander |

Breeding

Sexually mature slimy salamanders are easy to differentiate as the males have a large readily visible mental gland on the chin during the breeding season. Additionally, male slimy salamanders have papillose cloacal glands, but this is only readily visible under a magnifying lens. In plethodontid salamanders, the mental gland secretes hormones that increase receptivity for courtship in the female salamander (Houk et al., 1998). The hormones are transferred to the females by rubbing the mental gland and its secretions on the female's body, head, and nasolabial grooves. Adult females can be identified by the observance of eggs through the wall of the abdomen, or by the lack of a mental gland during the breeding season.

P. glutinosus immediately after hatching.

Depending on the latitude of origin, female slimy salamanders may breed either annually or biennially, with the more southern populations breeding annually. Sexual maturity is also linked to latitude, with the southern populations maturing faster. This may be due to the ability of the salamander to remain active longer and thus have a longer growing season. In southern populations, males may become sexually mature in one to two years as compared to four years in northern populations. Most individuals breed the year following sexual maturity. The majority of females in the southern populations reach sexual maturity at two years and lay eggs for the first time at three years, as compared to four years for maturity and five years to oviposition in northern populations. There are also differences in size at sexual maturity between the populations. The southern populations mature at a smaller size compared to the northern populations. For example, southern males are typically 1.6 - 2.1 inches (40-53 mm) snout to vent, while northern males are typically 2.1 - 2.8 inches (53-70 mm). Depending upon the latitude, the timing of egg deposition can vary from late spring and early summer in the northern portions of the range to late summer and early fall in southern populations (Petranka, 1998). However, courtship in the northern portions of the range can take place in the previous fall, with egg deposition taking place the following spring (Organ, 1968).

Gravid females will retain the eggs unless a suitable nesting site and medium are provided. In the wild slimy salamanders nest underground in burrows or in rotted logs. A loose deep substrate can be provided to allow the females to dig an appropriate nesting chamber. As an alternative, small burrows can be created from small diameter PVC and buried in the substrate. If the female salamander is frequently disturbed, the eggs may be retained indefinitely or laid and then abandoned. If the female retains the eggs, egg deposition can be hormonally induced. However, hormonally induced females rarely brood the eggs. Rearing of plethodontid eggs is a labor-intensive task with a high failure rate unless specialized equipment can be purchased. (Bernardo and Arnold, 1999).

Slimy salamanders are only occasionally available through the pet trade. Additionally, slimy salamanders purchased through the pet trade may also lack the requisite locality data to ensure that hybrids are not produced. If salamanders of unknown genetic background are produced then they should be labeled as potential hybrids to prevent accidental escape and interbreeding. Collecting slimy salamanders should only be accomplished after a through review of the regulations in the relevant state.

Plethodon variolatus, South Carolina Slimy Salamander |

Plethodon variolatus, South Carolina Slimy Salamander |

References

Bille, Thomas; 2000, Microhabitat utilization of the Mexican salamander, Pseudoeurycea leprosa, Journal of Herpetology, 34(4): 588-590

Bishop, Sherman C.; 1943, Handbook of Salamanders, Comstock Publishing, Ithaca

Brandon, Ronald A.; Huheey, James A.; 1975, Diurnal activity, avian predation, and the question of warning coloration in salamanders, Herpetologica 31:252-255

Brenner, Fred J.; 1969, The role of temperature and fat deposition in hibernation and reproduction in two species of frogs, Herpetologica 25(2): 105-113

Gabor, Caitlin R.; Jaeger, Robert G.; 1999, When salamanders misrepresent threat signals, Copeia 4:1123-1126

Gabor, Caitlin R.; 1995, Correlation test of Mathis' hypothesis that bigger salamanders have better territories, Copeia 3: 729-735

Dodd, C. Kenneth; 1989, Duration of immobility in salamanders, genus Plethodon (Caudata: Plethodontidae), Herpetologica 45(4): 467-473

Ferrier, Wayne; 1996, Salamander antipredator mechanisms, Reptile and Amphibian Magazine, 43: 48-54

Frank, Norman; 1991, Salamander Husbandry, Reptile and Amphibian Magazine, July-Aug: 56-60

Houk, Lynne D.; Bell, Alison M; Reagen-Wallin, Nancy; Feldhoff, Richard C.; 1998, Effects of experimental delivery of male courtship pheromones on the timing of courtship in a terrestrial salamander, Plethodon jordani (Caudata: Plethodontidae), Copeia 1: 214-219

Indiviglio, Frank; 1997, Newts and Salamanders, A Complete Pet Owners Manual, Barron's, Hauppauge

Jaeger, Robert G.; Gabor, Caitlin R.; 1999, Salamander social behavior, Reptiles magazine 7(7): 32-47

Jaeger, Robert G.; Fortune, Deborah; Hill, Gary; Palen, Amy; Risher, George; 1993, Salamander homing behavior and territorial pheromones: alternative hypotheses, Journal of Herpetology 27(2): 236-239

Jaeger, Robert G.; Joseph, Raymond G.; Barnard, Debra E.; 1981, Foraging tactics of a terrestrial salamander: sustained yields in territories, Animal Behavior, 29(4): 1100-1105

Landé, Susan Pritchard; Guttman, Sheldon I.; 1973, The effects of copper sulphate on the growth and mortality rate of Rana pipiens tadpoles, Herpetologica, 29(1): 22-27

Mathis, Alicia; Simons, Richard R.; 1994, Size-dependent responses of resident male red-backed salamanders to chemical stimuli from conspecifics, Herpetologica 50(3): 335-344

Ng, Melody Y.; Wilbur Henry M.; 1995, The cost of brooding in Plethodon cinereus, Herpetologica 51(1): 1-8

Organ, James; 1968, Time of courtship activity of the slimy salamander, Plethodon glutinosus, in New Jersey

Petranka, James W.; 1998, Salamanders of the United States and Canada, Smithsonian Institute Press, Washington

Powders, Vernon N.; Tietjen, W. L.; 1974, The comparative food habits of sympatric and allopatric salamanders, Plethodon glutinosus and Plethodon jordani in eastern Tennessee and adjacent areas, Herpetologica, 30(2): 167-175

Recios, George J.; 2001, Aquarium on the rocks, Fresh Water and Marine Aquarium, 24(1): 114-118

Richter, Klaus O.; 1993, Defense mechanisms in amphibians, Reptile and Amphibian Magazine, May-June: 41-46

Rossi, J., Rossi, J., 1994, General guidelines to reduce zoonotic disease potential associated with captive reptiles and amphibians. The Vivarium 5(96): 10-11

Rubin, David, 1969; Food habits of Plethodon longicrus, Herpetologica, 25(2): 102-105

Schaffer, Larry L.; 1995, Pennsylvania Amphibians and Reptiles, Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, Harrisburg

Sealander, John, A.; West, Boyce W.; 1969, Critical thermal maxima of some Arkansas salamanders in relation to thermal acclimation, Herpetologica 25(2): 122-124

Selby, Michelle F.; Winkel, Scott C.; Petranka, James W.; 1996, Geographic uniformity in agonistic behaviors of Jordon's Salamander, Herpetologica, 52(1): 108-115

Sever, David M.; Morphology and seasonal variation of the mental glands of the dwarf salamander, Eurycea quadridigitata, Herpetologica, 31(3): 241-251

Stebbins, Robert C.; Cohen, Nathan W.; 1995, A Natural History of Amphibians, Princeton University Press, Princeton

Townsend, Victor R. Jr.; Jaeger, Robert G.; 1998, Territorial conflicts over prey: domination by larger male salamanders, Copeia 3: 725-729

Vess, Tomalei J.; Harris, Reid N.; 1997, Artificial brooding of salamander eggs, Herpetological Review 28(2): 80

Wells, Kentwood D.; Wells, Roger A.; 1976, Patterns of movement in a population of the slimy salamander, Plethodon glutinosus, with observations on aggregations, Herpetologica, 32(2): 156-162

Whitaker Jr., John O.; Rubin, David C.; 1971, Food habits of Plethodon jordani metcalfi and Plethodon jordani shermani from North Carolina, Herpetologica 27(1): 81-86

Wright, K. M., 1993, Disinfection for the Herpetoculturist. The Vivarium 5(1): 31-33

Wright, K. M., 1994, Quarantine procedures for amphibians, The Vivarium 5(5): 32-33

© Ed Kowalski 2001