| Triturus marmoratus | |||||||||||||

| Marbled Newt | |||||||||||||

| Triturus pygmaeus | |||||||||||||

| Pygmy Marbled Newt or Southern Marbled Newt | |||||||||||||

Triturus pygmaeus |

|

||||||||||||

Note on taxonomy: At the time this sheet was written, the marbled newts were considered a single species with two subspecies. T. marmoratus and T. pygmaeus are now considered to be two separate species.

Description

Unlikely to be mistaken for any other species of Triturus,

the Marbled Newt is one of the largest newts in its

genus, with specimens of Triturus marmoratus

marmoratus over 17 cm total length known. T.

m. marmoratus normally reaches 14-15 cm at adulthood, though this varies with the geographical origin of the animals. T. m. pygmaeus, the Pygmy

Marbled Newt, rarely exceeds 11 cm when adult. Some

consider this a species in its own right, but I will

treat it as a subspecies for the purposes of this

information sheet. In both subspecies, the female

is usually slightly larger than the male. Both

newts are quite robustly built, with small warts on the

velvet-like skin during the terrestrial stage and

smoother skin when aquatic.

Both subspecies have varying amounts of green mixed with black. Some animals are predominantly black with green blotches, while in others, the reverse is the case. The underside is dark brown or black in the nominate form, with small white spots, while in T. m. pygmaeus the underside has larger white spots and small cream-yellow marks. Juveniles and adult females have an orange stripe running along the back from the base of the head to the end of the tail. Males of a given population tend to have a darker green colouration than females from the same population, and this is noticeable prior to sexual maturity. Some populations of T. m. pygmaeus in Spain and Portugal are bronze rather than black, particularly during the breeding season.

Even outside of the breeding season, adult males have the remnants of their crest as a noticeable ridge. The crest of the nominate form is quite tall and smooth (not jagged like the crested newts) with dark vertical banding. The crest dips noticeably at the base of the tail before rising again along the tail. This is less pronounced in T. m. pygmaeus, and this subspecies also has a lower crest than the nominate form. Females don't have a dorsal crest, but their tail fin becomes much higher during the breeding season.

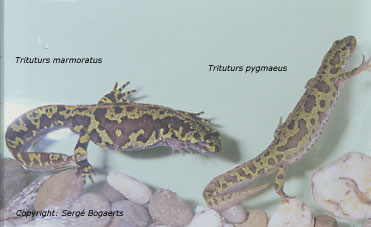

Comparison of T. marmoratus marmoratus and T. marmoratus pygmaeus

This species is closely related to the crested newts (Triturus cristatus, T. karelinii, T. carnifex, T. dobrogicus) and naturally hybridises with T. cristatus where the two overlap in northern France. T. marmoratus, along with the crested newts, also suffers from the genetic defect that causes 50% of embryos to die at the stage of tail bud formation.

Breeding usually takes place from early to late spring (late February to late May in northern France), though it varies greatly with habitat and latitude. In the warmer and drier parts of Spain and Portugal, the breeding season coincides with the cool and wet months of the year (mid-winter). In the wild, sexual maturity is reached at 4-7 years.

Habitat for T. marmoratus and otherTriturus species in France.

Natural Range and Habitat

T. m. marmoratus is found from France into

northern Spain and Portugal, though it is absent from parts of the

Pyrennese mountains in southern France and northern Spain.

In central and southern Portugal and the southern half of Spain, the nominate form is replaced by T. m. pygmaeus.

The nominate form is relatively aquatic in comparison to some other Triturus species (e.g. the small-bodied newts), with both adults and juveniles regularly visiting ponds. Their normal habitat is deciduous or mixed woodland, where they can frequently be found in numbers under dead and rotting wood, and other hiding places. They emerge from these refuges in the late evening and are primarily nocturnal. In central and southern Spain, the warm climate and drying up of their breeding ponds often forces T. m. pygmaeus to aestivate for much of the summer.

Male T. marmoratus marmoratus is identified outside of breeding season by small crest ridge. |

Female T. marmoratus marmoratus. When threatened, these newts release toxin (white specks) from glands along the back and sides. |

Housing

There are a number of ways to maintain these newts.

Perhaps the most successful is the large semi-aquatic

setup. A 120 cm long x 40 cm tall x 30 cm wide

aquarium (48 x 16 x 12 inches) that is 50% water and 50%

land is ideal for three pairs (note that males are

relatively aggressive in the breeding season so you could

keep more females than males in such a setup).

Alternatively, some people maintain their adults in

aquatic conditions all year round, only providing a small

floating island for the newts to emerge onto. My

own preference is to keep adults and juveniles

terrestrially except for the breeding season, at which

time I keep the adults in fully aquatic conditions with a

small island. The water should be as deep as

possible during the breeding season (25 cm / 10 inches

should be the minimum).

These newts are still-water animals, so avoid strongly flowing water. Southern individuals will tolerate temperatures up to 80°F for short periods of time, but a fall in temperature at night is essential. Ideally, these newts should be maintained at no more than 25°C (77°F) during the warmest part of the year. In winter, a temperature of 4 or 5°C (39°F) should be considered the minimum. T. m. pygmaeus may benefit from slightly warmer temperatures in the winter.

T. marmoratus marmoratus. |

T. marmoratus marmoratus with unusually yellow coloration. |

Because they live in wooded areas in the wild, if kept terrestrially, I use a substrate of compost and soil with assorted pieces of bark and moss to hide under. These animals are quite gregarious when terrestrial, so don't be surprised to find many in one hiding place when there are many hiding places available. Lighting is not essential and I don't use any. The terrarium should never be allowed to dry out completely, so lightly mist the tank when you see the substrate start to become dry. A water bowl can help prevent complete drying out, but be sure that the newts can enter and leave it without problems.

Note on ventilation: A number of enthusiasts have found that these newts can develop skin problems if kept in moist conditions but without sufficient ventilation. For this reason, I advise you to use a screen/mesh lid on your terrarium. This allows moisture to escape, but it gives the required ventilation.

If kept in an aquatic setup, a heavily planted tank with a sand or large gravel substrate is ideal. In the semi-aquatic setup, a mixture of both setup types is indicated.

Male T. marmoratus marmoratus in breeding dress. |

Triturus marmoratus pygmaeus. |

Feeding

Feeding usually takes place at night. When

terrestrial, these newts will take crickets, waxworms,

earthworms (not the red-ringed species though), white

worms, fruitflies, etc. I advise you to gutload

crickets with flaked fish food prior to feeding.

Mineral supplements are not required, particularly when

employing gut-loaded crickets or a varied diet.

When kept aquatically, these newts will also eat frozen

bloodworms, blackworms, Daphnia and the usual fare.

T. marmoratus marmoratus male. |

T. marmoratus marmoratus female with eggs. |

Breeding

A very noticeable period of cooling is necessary for all

but the most southerly populations to breed.

Keeping well fed adults in a terrestrial setup containing

lots of moss and wood is ideal. Keep the animals at 5°C (40°F) for 2-3 months. If well fed

prior to this cooling period, feeding shouldn't be

required and indeed, the animals will probably ignore

food. After the cooling period, warming to 10-15°C (50-59°F) should result in the

animals entering breeding mode after a few days.

Then transferring them to a large aquatic setup with an

island is advised (put them on the island and let them

enter the water when they wish). Mating behaviour

begins over the coming few weeks and can continue for

months, the adults only leaving the water in late May or

early June. Courtship is similar to that of the

other large-bodied Triturus, involving tail-fanning

and the characteristic "cat-buckle" position.

Females may mate several times with various males and

eggs are laid over a period of weeks to months, with a

total of 200-250 eggs being an average number, though

sometimes in excess of 350 are laid.

Newly-hatched T. marmoratus larvae. |

T. marmoratus larva. |

The eggs and the larvae should be maintained at a similar temperature to that of the breeding aquarium. As mentioned above, expect to lose 50% at tail-bud formation due to a chromosome problem that these newts have. The eggs are unpigmented, and they usually hatch 14-21 days after laying. The 8-10 mm larvae are very pale cream or white in colour, with two dark bands running lengthwise from the head onto the tail, one on either side of the dorsal fin. After yolk absorption (3 days or so), the larvae become active mid-water predators, and live food is essential (young Daphnia, newly hatched brine shrimp/Artemia, ostracods, Cyclops, etc). Growth is rapid, and metamorphosis is usually reached at between 8 and 10 weeks if fed well. Metamorphs of the nominate form are typically 5-8 cm, while those of the Pygmy form are noticeably smaller. The metamorphs can be raised on gut-loaded hatchling crickets, white worms and fruitflies. Sexual maturity in captivity typically takes 2-4 years.

Triturus marmoratus marmoratus

juveniles

References

Richard A. Griffiths (1996) Newts and Salamanders of

Europe. T&AD Poyser Natural History.

Sergé Bogaerts, Nymegen and E. Uchelen (1996) Urodela info 9 (3-5).

Marc Staniszewski (1995) Amphibians in Captivity. TFH Publications.

© 2001 John Clare. Posted June 2001.